Bookshelf: Books and Documents

Canadian Art

These works are representative pieces of the country's most famous artists. Canadian art often focuses on wilderness and geography themes. See https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/ for details on many authors, etc.

Famous Artists to know

- Group of Seven, esp Lawren Harris https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/canada/articles/who-were-canadas-group-of-seven-2 & https://thegroupofseven.ca/ (has excellent overviews of each)

- Emily Carr https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/emily-carr/key-works/forest-british-columbia/

- Thom Thompson https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/tom-thomson/key-works/the-jack-pine/

- William Kurelik https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/william-kurelek/key-works/reminiscences-of-youth/

- Robert Bateman https://www.artcountrycanada.com/bateman-robert-midnight-black-wolf.htm

- Maud Lewis https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/maud-lewis/key-works/winter-sleigh-ride/

Additional famous works

- CW Jefferys: Arrival of Radisson https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_William_Jefferys#/media/File:Arrival_of_Radisson_in_an_Indian_camp_1660_Charles_William_Jefferys.jpg

- Harris: A Meeting of the School Trustees https://www.gallery.ca/sites/default/files/styles/ngc_crop_16x9_1600px/public/canadian-art.jpg?itok=6NS679j2×tamp=1741206963

- Chambers: 401 Towards London https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/jack-chambers/key-works/401-towards-london-no-1/

- Colville: To Prince Edward Island https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/alex-colville/key-works/to-prince-edward-island/

- Riopelle: Pavane https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/jean-paul-riopelle/key-works/pavane-tribute-to-the-water-lilies/

- Pratt: Supper Table https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/mary-pratt/key-works/supper-table/

- Chee-Chee: Goose in Flight https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/benjamin-chee-chee

- McCarthy: Rockglen Saskatchewan https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/doris-mccarthy/key-works/rockglen-saskatchewan/

- Brymner: The Coast at Louisbourg https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/william-brymner/key-works/the-coast-at-louisbourg/

- Krieghoff: Merrymaking https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/quebec-city-art-artists/key-artists/cornelius-krieghoff/

Professionalism in Student Interactions

Be sure you are pronouncing students’ names correctly, using the form of their name they prefer if they also go by a shorter version, and avoiding fun nicknames or pet names.

Personas to avoid falling into:

The Cool Teacher—don’t try to dress or act like your students in an attempt to be accepted

The Young, Relevant Teacher—don’t mimic student trends; this will actually alienate students

The Important Authority/The Professor—don’t try to project superiority through big words or sarcasm

The Flirt/The Creepy Teacher—avoid sitting with opposite-gender students, having conversations in closed rooms, or repeated one-on-one talks

The Best Friend/Youth Counselor—don’t undermine your authority by over-mentoring certain students

The Mocker—don’t mock cultural norms or join in when students are making fun of something

Aim to be mature, secure, and stable. Be interested in your students’ lives, bless the overlooked, and encourage freely.

Dress neatly and professionally. You should be dressed a level up from what your students are (e.g. wear a full button down if students are required to wear polos, etc.)

Remember that if your students see you outside of school, your actions should always be responsible and above reproach.

Avoid interacting with students online/through social media.

Sources

Relating to Students 2.0 by Jeff Swanson Relating to Students 2.0 - The Dock for Learning

Communicating with Students

Be aware of your own tendencies. If you are a task-oriented person who tends to prioritize tasks over people, make sure that in your zeal to do all the things necessary to give your students a quality education you aren’t missing their hearts

Practical ways to relate to students:

Greet your students at the door in the morning—look each student in the eye and greet them by name as they enter the classroom

Allow time for students to tell their stories—let your students talk about the things that are important to them (while still having limits to ensure you aren’t wasting a lot of class time)

Write notes to your students—praise a student for something positive you noticed or encourage a way you’ve seen them working hard recently

Be interested in the things that interest your students—put effort into learning about their hobbies and interests

Pay attention to your students’ moods and emotions. Pause if a “fine” response feels off and be willing to listen to what’s going on in your students’ lives.

Sources

Relational Practices for Task-Oriented Teachers by Rosalie Beiler Relational Practices for Task-Oriented Teachers - The Dock for Learning

Relating to Students 2.0 by Jeff Swanson Relating to Students 2.0 - The Dock for Learning

Staff Meetings

Meetings provide an opportunity for clear communication, effective planning, fruitful discussion, and professional development

Attend a meeting ready to listen to others, focus on the task at hand (silence technology or other distractions), and offer your own input

Regular meetings as staff help to create an environment of teamwork and support. Teaching is emotionally expensive and lonely, but interacting with each other as staff can combat burnout and provide fresh inspiration.

Foster growth by exploring the following:

Set personal goals—what can change tomorrow? What are your quarterly visions?

Discuss staff-wide vision—how can you make the school different next year? What aspects of school culture need to change?

Strategize—what is something that you’ve “always done this way” that needs to change? Where can you broaden your perspective?

Reasons to include professional development in staff meetings:

Giving teachers opportunities to grow in the craft of teaching can prevent burn-out

The intentional developing of teachers’ skills is to your school’s advantage

Practical tips for using staff meetings as opportunities for professional development:

Have guest speakers come in to talk about an area of expertise

Use pedagogical books as a framework for learning and discussion

Pull from staff strengths—have teachers talk about areas they have invested into and can present techniques to others

Sources

Why Meet? How Effective Meetings Can Build Your School Culture by Philip Horst Why Meet? How Effective Meetings Can Build Your School Culture - The Dock for Learning

Staff Development: Empowering the Educator to Engage the Learner by Howard Lichty Staff Development: Empowering the Educator to Engage the Learner - The Dock for Learning

We Love a Challenge: Promoting Staff Development by Ken Kauffman We Love a Challenge: Promoting Staff Development - The Dock for Learning

Maximizing After-School Chat Time by Ryan Hoover Maximizing After-School Chat Time - The Dock for Learning

Parent Teacher Meetings

Before the Meeting

Recognize the purposes of parent-teacher meetings:

To establish common ground between the parents and teacher

To create an opportunity for parents and teachers to communicate on a constructive level (rather than only once there is a problem)

To facilitate collaboration and teamwork in caring for the child

If you feel nervous, remember that the parents likely do, too. As one principal said, “You think you’re nervous? It’s not even your child you’re talking about. The parents are just as nervous as you are because it’s their child and they’re the ones that are responsible.”

Neither the teacher nor the parent is on trial. It’s a time of communicating and learning to see things from the parents’ perspective.

Pray over the conferences—pray for wisdom, clear communication, and understanding.

Consider an alternative to you sitting on one side of your desk and the parents on the other side. It can feel intimidating to parents who feel like they are a student again, and the desk can feel like a barrier. Place their chairs to the side of your desk or sit around a table.

During the Meeting

Always begin with a positive comment (encouragement, something the child is doing well, a way they contribute well to the classroom, etc.)

There is value to discussing “small issues” too. Don’t wait until something is a big problem to bring it up. It’s easier to deal with something early and in a non-threatening way. You could say, “This isn’t a big deal, but it could become a big deal if we let it go. I started to notice this student has this problem. What can I do about it? What can you do about it? What works at home in dealing with this sort of problem?”

There should be no surprises. If Beth is struggling in math, her parents should already be aware of this through prior communication. Do not assume they have figured it out.

Aim to spend at least as much time listening as you do talking. Parents need to feel heard. Also, they are the expert on their child, and you can learn from them.

Remember that parents do want to know how their child is actually doing. It is hard to tell them of difficulties, but it is important. Present problems in a helpful and supportive manner, not accusing or blaming the parents.

Talk about all aspects of the child’s person—academic, social, spiritual, and personal growth.

Ask questions. Prepare your questions beforehand. Here are some examples:

What does Billy say about school?

Is there anything about school that has been particularly stressful for him? How can I help?

What are areas you’d like to see him grow in right now?

Is there anything you want me as a teacher to know about your child?

How much time does your child spend on homework each night? How do you feel about this amount of homework?

Due to time constraints, some teachers prefer to ask some of these questions in the form of a paper survey the parents can fill in and submit later. See the following example: https://thedockforlearning.org/document/classroom-survey-for-parent-teacher-fellowship/

Read this article for one seasoned teacher’s step-by-step description of how she runs a parent-teacher meeting: https://thedockforlearning.org/parent-teacher-conferences-part-two/

Sources

You Are Not on Trial: How Parent-Teacher Events Can Strengthen Your Teaching by Victor Ebersole You Are Not on Trial: How Parent-Teacher Events Can Strengthen Your Teaching - The Dock for Learning

Parent-Teacher Conferences by Arlene Birt Parent-Teacher Conferences, Part One - The Dock for Learning Parent-Teacher Conferences, Part Two - The Dock for Learning

Communicating with Parents

Establish a Foundation of Respect

Approach conversations with parents with compassion. Remember that parents can feel vulnerable, like failings in their children are direct reflections of them as parents. Emphasize your desire to work together with the parents to help the child thrive.

Come to the conversation with a posture of curiosity and a desire to truly hear what the parents have to say (not just share your own opinions). Ask lots of questions and consider planning your questions beforehand. This approach respects parents’ perspectives and reduces resistance.

Recognize your place in the layers of authority at play. You are in a position of service under the authority of God, the local church, the school board, and the parents.

Consider a proactive approach, in which you contact parents before the school year to learn about the child’s strengths, challenges, and effective discipline methods. This partnership approach acknowledges parents’ expertise.

Don’t let the only time parents hear from you be when something is going wrong. Send an email or pick up the phone to tell them about good behavior, too. Affirm the strengths you see in the child.

Regular, ongoing communication is valuable. Consider sending frequent progress reports detailing character growth or academic progress, regular newsletters, or a systematic personal contact with parents (e.g. sending an email to a different parent at the end of each day mentioning something you appreciated about their child that day).

Tips for Communicating Clearly

Mirror and summarize what you hear the parents saying throughout the conversation. This reflects an openness to truly listen and a clear attempt to ensure understanding. Try phrases like, “I think I hear you saying (summary of what was said). Did I hear you correctly?” “I’m not sure if I understood what you were saying about x. Could you talk more about that?” “I agree with what you said about x. What would you say about y?”

Be honest—even when it’s difficult. Parents are trusting you with their precious children, and part of that includes trusting that you will communicate with them what they need to know.

Practical advice for positive communication:

Make early positive contact—build rapport before addressing issues

Use a positive tone—avoid overly critical language about students (this can trigger a parent’s naturally protective instincts)

Use the sandwich method—offer a positive comment before and after sharing any negative feedback

Understand the parents’ perspective—recognize that parents see children as their most precious possession

Be prepared and solution-oriented: come to parent meetings with documented observations and potential solutions

Show a posture of humility—be quick to apologize for any mistakes and listen humbly to criticism

Other Considerations

Recognize the following possible barriers to parental involvement:

Intimidation by education—parents may feel intimidated due to their own negative school experiences, cultural devaluation of education, or perceiving teachers as “smart”

Separation of home and school—some parents, due to cultural norms, see home and school as separate, unaware they can contribute

Perceived inability to help—parents may feel incapable, especially when helping students with homework, fearing they’ll appear inferior to their child

Set boundaries if a parent situation becomes volatile or you are dealing with persistent parent harassment. Be quick to involve the administrator or members of the school board.

Sources:

Relating to Parent Families and the Local Church by Glendon Strickler Relating to Parent Families and the Local Church - The Dock for Learning

Facilitating Open Communication with Parents by Jason Croutch Facilitating Open Communication with Parents - The Dock for Learning

Cultivating Conversations by Anna Zehr Cultivating Conversations - The Dock for Learning

What Parents Want Most from Teachers by Shari Zook What Parents Want Most from Teachers - The Dock for Learning

Naughty Students, Naughty Parents, and Naughty Teachers! By Jeff Swanson Naughty Students, Naughty Parents, and Naughty Teachers! - The Dock for Learning

Teacher Ties with Parents by Norwood Shank Teacher Ties with Parents (Norwood Shank) - The Dock for Learning

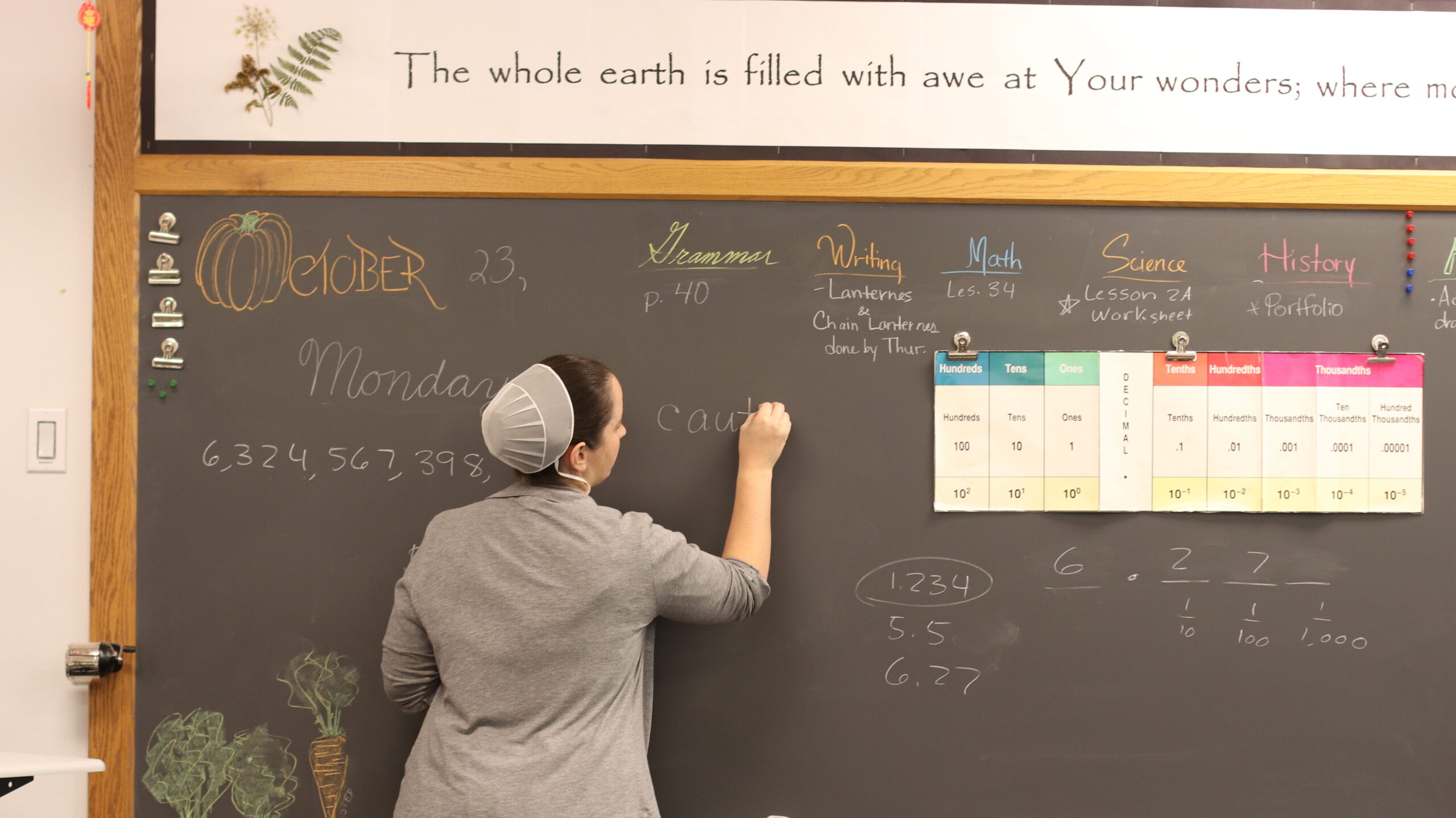

Board Work

Your chalkboard or whiteboard is an amazing tool that you use every day—it is worth investing time and intentionality into using it well.

Keep boards clean. At least once a week, wipe them down with water and then a dry cloth. Dirt and smears distract from your teaching. (Note: many teachers have noticed that any kind of cleaner eventually takes the smooth shiny finish off whiteboards. Just use water!)

Erase often. The more white space there is, the less distractions there are, helping students to focus on the task at hand.

As much as possible, use neat handwriting. You are modeling for your students what you expect their writing on their written assignments to look like. Demonstrate this every time you write on your board.

After orally presenting the main point of your lesson, demonstrate the concept you just taught on the board. This gives students both an oral and visual presentation.

Go slowly. It might be easy for you, but it is new and confusing to students.

Pause between steps. This gives the students a chance to comprehend at their own speed or think on their own about what step comes next.

You can let students practice a new concept on your board, giving them valuable guided practice.

Don’t neglect to use the board for diagrams, billboards of dates and persons in history class, showing cause and effect, or illustrating chronological order.

Sources

Tool Tips: Chalkboards and Whiteboards by Deana Swanson Tool Tips: Chalkboards and Whiteboards - The Dock for Learning

Asking Questions

The “Why” of Question-Asking

Asking good questions is a powerful learning tool that is often under-utilized. With intentionality, the questions you ask your students can provide valuable learning opportunities.

The “What” of Question-Asking

Recognize that there are different types of questions.

Some questions are fairly simplistic, asking for basic information or recall. These types of questions are well-suited to situations like a review session or parts of math class.

Some questions go deeper and require higher-level thinking. These types of questions rarely have one “right” answer, but are more open-ended, asking students to apply knowledge and draw connections.

Allow a wait time of three to five seconds for students to form a response. Calling on a student too soon or moving too quickly to the next person denies the child enough time to retrieve the information and deprives the brain of interaction with the question.

Cold calling (the practice of calling on a student randomly, not simply choosing one who has raised their hand) is a valuable technique. However, make sure you ask the question first before using a student’s name. Saying the name first, such as, “Carl, what is the purpose of photosynthesis?” can cause everyone who isn’t Carl to shut their brains off since they already know they don’t have to answer.

The “How” of Question-Asking

Plan your questions before class and write them down instead of trying to come up with good questions while teaching.

Beware of approaching asking deeper-level questions like a softball game, where you as the teacher “pitch” the question to the student, and they either hit the ball or strike at it, and that’s the end of the interaction. Instead, view asking questions more as a game of volleyball, where there is a lot of back and forth between you and the students, and you direct follow-up questions to other students as well.

For example, asking a question might look something like this:

Teacher: Asks question

Student 1: Answers

Teacher: “Student 2, do you agree or disagree? Why?”

Student 2: Responds

Teacher: “Student 3, do you have anything to add?”

Ask follow-up questions to extend student responses. For example:

What makes you say that?

How do you know that to be true?

Can you say more about what you’re thinking here?

Why is this important?

Can you explain how you came to that conclusion?

Allow students to interact with questions in various ways:

Group response: for one-to-three-word definitive answers, ask students to respond as a group. It is helpful to have a hand signal that prompts them to say the answer, that way you can control the wait time.

Partner response: if the needed answer is less objective or is longer than a few words, have students tell the answer to their partners. You can tune into their responses or ask a few students to share their response afterwards.

Written response: for a deeper-level thinking question, have students write down their answers before asking a few students to share their thoughts. This allows students to process their thoughts before needing to share them aloud and will enrich class discussions.

Further strategies for using questions (adapted from J. Doherty’s book Skillful Questioning)

On the Hot Seat: Students take turns sitting in the “hot seat” and answering questions.

Ask the Expert: The teacher asks questions of a student on a given topic and encourages other students to also ask questions.

Ask the Classroom: Display questions to encourage thinking about pictures or objects in the classroom.

Phone a Friend: A student calls on a fellow-student to answer the teacher’s question. The first student also gives an answer.

Eavesdropping: The teacher circulates in the classroom, listening in on groups, and asking questions based on their discussions.

Question Box: The teacher has a box containing a series of questions. At the end of the day, or end of the week, take some time to choose a few questions for class discussion.

What is the Question? The teacher provides the answer and encourages students to determine the question.

Sources

I Have a Question! by Arlene Birt I Have a Question! - The Dock for Learning

Pedagogical Moments: Questions by Carolyn Martin Pedagogical Moments: Questions - The Dock for Learning

Leading Class Discussions

Stimulating, productive discussions are among the most rewarding classroom experiences for both teachers and students. Teachers can use specific strategies to ensure that a discussion doesn’t flop, either due to the excruciating silence of unresponsive students or the uncontrolled chaos of too many students talking at once.

Before the Discussion

Plan questions beforehand. Here are general types of questions that are useful in many situations:

“What connections do you see between _____ and _____?”

“What do you think about_____?”

“How would you feel if _____?”

“How would you respond to _____?”

“Can you explain _____?”

“What would cause ______?”

“What would be the consequences of _____?”

It is important to establish clear procedures. Before the first class discussion of the year, explicitly spell out how you expect your students to behave. Some examples of expectations you might establish include the following:

Instruction on what types of responses are relevant and what is distracting

Establish an environment of respect where students speak in turn and listen to each other

Demonstrate what respectful listening looks like and require it of all students (keep your own mouth closed, turn to face the speaker)

Develop hand signals to show students when you specifically do or do not want them to raise their hands before answering

During the Discussion

While a class discussion is inherently student-centered, you as a teacher still play an important role in helping the discussion to be fruitful.

Know your students—be aware of which students are likely to speak too much, which students will get overlooked, and which students are potential troublemakers.

Be prepared—in a lecture, you can decide what content you will cover. In a discussion, you will need to be prepared to explore any issue reasonably related to the discussion topic.

Begin the discussion—set the tone with a thoughtful question, controversial comment, or shared experience of reading an article or watching a video clip.

Ask questions—ask a student for clarification, to support his comment or opinion, or to respond to what another student has said.

Provide summaries—provide periodic summaries of what has been discussed so far.

Reflect—either as a group or on your own later, reflect on what worked well and what you might do differently next time.

Not all responses need to be verbal. A quick raise-of-hands poll such as “Raise your hand if you think _____. Now raise your hand if you think _____ instead,” can get all students thinking and responding without saying a word and often leads to productive comments from students who wish to explain their responses.

As long as it is sincere and relevant, every student response is a good response. Even when a student answers a question incorrectly or gives a comment that reflects faulty understanding, he deserves to be recognized and encouraged for making an effort to engage with the material and connecting it with his prior knowledge to the best of his ability.

Sources

Cultivating Healthy Class Discussions by Peter Goertzen Cultivating Healthy Class Discussions - The Dock for Learning

Effective Classroom Discussions IDEA Paper 49 Effective Classroom Discussions - The Dock for Learning

Lesson Planning

The Basics of Lesson Planning

A goal without a plan is only a dream. If you have a goal of teaching your students something, but no concrete plan for how you’re going to get there, your chances of actually achieving your goal are greatly diminished.

When planning a lesson, don’t simply ask yourself, “What will we do tomorrow?” That question leads to activity-based learning (for example, “we’ll read from our readers” or” we’ll complete a worksheet”). Instead, ask yourself, “What will my students learn?” This focuses on teaching a concrete body of information or a new skill.

Lessons should begin with some sort of “hook” to draw the students into the lesson and ignite their interest. It may be a short demonstration, question, joke or funny anecdote, interesting fact, object or prop that relates to the lesson, etc.

Many taught lessons naturally follow a pattern of direct instruction (you as the teacher presenting information or teaching a skill), guided instruction (giving the students an opportunity to worth with that information or skill in a structured and supported way), and independent practice (allowing each student to work with the new concept on their own). Another way of framing this is thinking in terms of “I do, we do, you do.”

Objectives

Making objectives is very important in lesson planning. An objective is a written statement of what the students will learn as a result of your teaching.

Objectives can be written in terms of “The student will be able to . . .”

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a helpful tool in writing objectives. It provides a framework of six cognitive processes, listed in order from lower order thinking skills to higher order thinking skills: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create. In each of the six categories, there are suggested verbs you can use in your objectives to most accurately describe what you want your students to be able to do by the end of the lesson.

The following resource may be helpful in using Bloom’s Taxonomy: Bloom Writing Objectives - The Dock for Learning

Lesson objectives must begin with the end in mind. Before you can plan an effective lesson, you need to think about where you’re planning to go. Know exactly what you are trying to teach your students and what you’re going to do to get there.

Objectives keep you from generating a lot of activity without a purpose. Instead of just doing things and hoping that some of them will be productive, planning your objectives allows you to focus your energy in a specific direction.

Follow the three M’s of objectives (borrowed from Doug Lemov):

Manageable: the objective should be written in a way that it can be achieved in one day’s lesson.

Measurable: the objective should be written in a way that your students’ success can be determined. At the end of the lesson, can you tell whether the objective has been met?

Made first: the objective should be determined before you decide how you’re going to reach that objective. You should know what you want to teach before you decide what activity or assignment you’re going to use to teach it.

Textbook publishers often provide their own objectives, but you may need to adapt those to fit your classroom and students.

Assessments

Another component of lesson planning is knowing how you will assess whether or not you have met your objectives.

Assessments may come in the form of written assignments, group work, worksheets, etc. An assessment is any way that you can check for student understanding.

Objectives ask “What will the student know?” Assessments ask, “How will I know whether or not they know it?”

Other Advice

Whenever possible, try to connect new knowledge to students’ previous knowledge. This builds a scaffolding of learning that makes learning new information more intuitive and leads to better retention.

Whenever possible, avoid planning each day’s lesson in isolation the day before you teach it. If you can think in longer sections of what you’re attempting to teach, it will enable you to build lessons off each other and connect to previous learning in ways that will strengthen your teaching and greatly aid your students’ understanding.

Sources

The 4 M's of Effective Objectives: Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them - The Dock for Learning

What Do Teachers Do? Focusing Your Lessons with Objectives - The Dock for Learning

The Victorian Age

This PowerPoint presentation introduces the history and themes of the Victorian Age in English literature.

Download the presentation now or view it below.

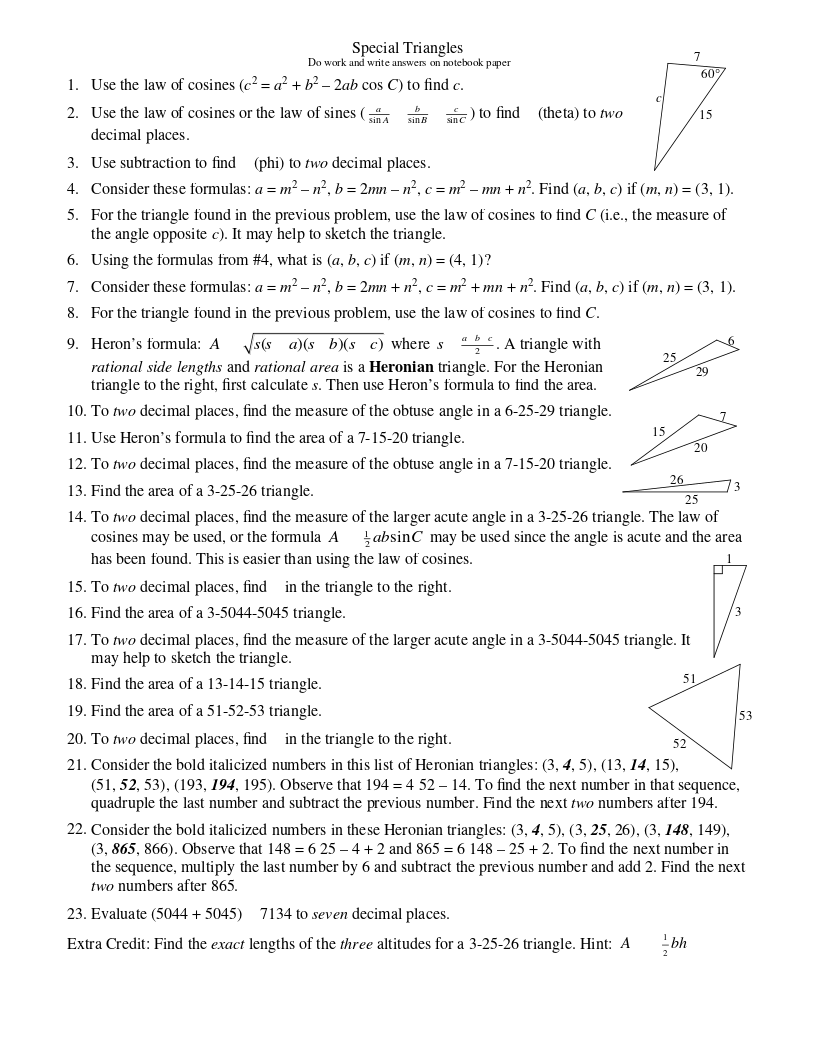

Special Triangles

This enrichment activity looks at three special types of triangles with side lengths that are all whole numbers. One type of triangle has a 60° angle. Another type has a 120° angle.

For the third type of triangle, the area is also a whole number. Such a triangle is a Heronian triangle. Much of the activity focuses on Heronian triangles.

Two types of Heronian triangles are emphasized. The one type is almost equilateral. The other type has one side that is 3 units long.

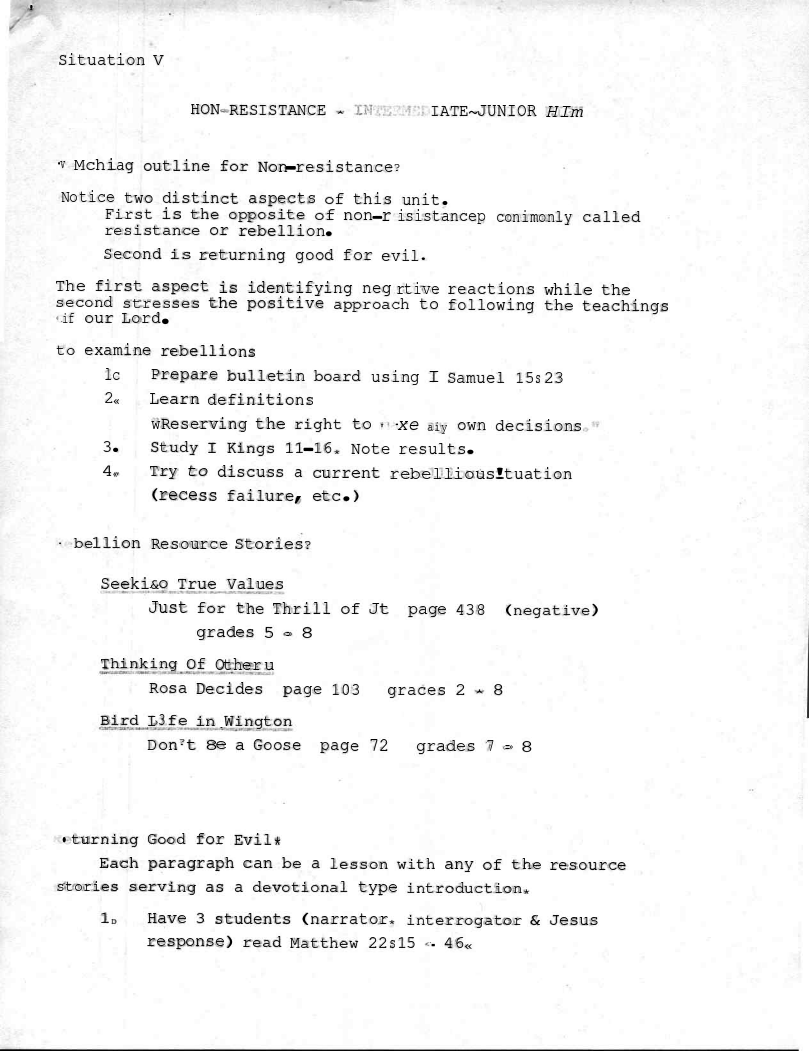

Non-resistance

What is the opposite of non-resistance? Created in the 1970's for Manheim Christian Day School, this fifth "Situation" from the Kingdom Values series addresses rebellion. The plan provides discussion strategies for discipling intermediate and junior high students in the non-resistance of Jesus.