All Content

Psalm 119:65-72 TETH

The text of Psalm 119:65-72, sung acapella. The arrangement is by Michael Owens and Frederick Steinruck. The text: Thou hast dealt well with thy servant, O Lord, according unto thy word. Teach me good judgment and knowledge: For I have believed thy commandments. Before I was afflicted I went astray: But now have I kept thy word. Thou art good, and doest good; teach me thy statutes. The proud have forged a lie against me: But I will keep thy precepts with my whole heart. Their heart is as fat as

Psalm 119:25-32 DALETH

The text of Psalm 119:25-32, sung acapella. The arrangement is by Michael Owens and Frederick Steinruck. The text: My soul cleaveth unto the dust: Quicken thou me according to thy word. I have declared my ways, and thou heardest me: Teach me thy statutes. Make me to understand the way of thy precepts: So shall I talk of thy wondrous works. My soul melteth for heaviness: Strengthen thou me according unto thy word. Remove from me the way of lying: And grant me thy law graciously. I have chosen the

Old Fashioned Games for Dreary Days

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on UnsplashIn our neck of the woods, “November” is our shorthand for “bleak days with unremitting gray skies and lots of rain.” Sometimes we say “No” because that’s even shorter. But it doesn’t change anything.

What do you do with energetic children when the weather is too drippy to go out?

Here are some old-fashioned games we used to play when I was a kid. They’re good for corralling a herd of young’uns when you don’t have access to a gym or the great outdoors. I’m sure there are infinite variations; I’m explaining the simplest rules I know. Feel free to improvise and use what you have on hand.

Michael Finnegan

One person is chosen to be “It” and leaves the room. The rest agree on an action he must take upon his return – such as closing an open book, patting someone on the shoulder, or turning on a light switch. When he comes back into the room, they begin to sing Michael Finnegan or another nonsense song, on repeat. When he comes close to the thing he must do, they lower their voices. When he moves to the wrong part of the room, they sing louder. When he does the right thing, everyone stops singing and cheers. It seems impossible that he could guess, but who can decipher the secret coding of childhood? (all ages)

Swat

Need I say more? If you don’t know, ask your students how to play. In my childhood, we used a rolled up newspaper to hit the knees. In Europe, I found they used an empty plastic pop bottle on the head. Yikes. (all ages)

Jump Rope Games

Jump ropes are good for a lot of games besides individual skipping. Google it. Here are some ideas to get you started. (age 6+)

Hide the Thimble

Like hide and seek, only hiding one thimble instead of many persons. Everyone tries to find it; the one who does hides it next time. (< age 8)

Winker

Everyone sits in a circle and receives a penny; the one whose penny says 1982 (or another chosen date) is the Winker. When the game begins, he tries to wink surreptitiously at anyone in the circle. If they see him wink at them, they must throw their penny into the middle of the circle. They have been eliminated. If they see him wink at someone else, or in general feel he is behaving suspiciously, they may say, “I suspect.” Someone else may say, “I agree.” The one who suspected then says his guess – “James Smith.” If the second person disagrees, the moment passes. If she agrees, James Smith is asked if he is the Winker. If they are correct, he is eliminated and everyone else wins. If they are wrong, the one who suspected him is eliminated, and the game goes on until a) the correct Winker is found and dispatched, or b) the Winker has eliminated all but one person. Multiple Winkers may be added for larger groups. If a Winker winks at them, they simply wink back and keep playing. (age 8+)

Farmer in the Dell

Everyone stands in a circle and holds hands to march around the farmer while singing The Farmer in the Dell, with a new person picked each time to be the farmer’s wife, the child, the dog, and so on. The circle narrows each time, as one more person moves to the middle with the farmer. (< age 10)

Animal Sound Match

Slips of paper are made ahead, with the name of an animal on each slip, but only two alike for each kind. (Pig, pig, horse, horse, sheep, sheep.) On the count of three, each person starts making the sound their animal makes, and trying to find the other person who is making the same noise. The game ends when everyone finds a match. (< age 10. I’ve known teenagers to play it, but only in the right mood.)

Congress

The group divides into smaller groups, with four or five people in each. In each round, one person from each group is sent out of the room. These “Congress members” collaborate in choosing an item to remember in their heads – as simple as a pumpkin, or as complex as George Washington’s thumbnail. They return to their groups, and answer rapid-fire questions to guess the item, answering only yes or no. The first group to guess the correct item wins, and new delegates are sent out of the room. (age 10+)

Nursery Rhyme Game

One person is chosen to be “It” and leaves the room. The rest pick a well-known nursery rhyme and are each assigned a word from it, possibly skipping nonspecific words like “the, it, and, or, etc.” So in order, children may have “Jack, Jill, up, hill, fetch, pail, water” and so on. When the It person returns, he asks any of them a question. “What did you have for lunch today?” Or, “Where did you buy your blue jeans?” They may answer truthfully or fancifully, but their answer must include the nursery rhyme word they were given. “I cooked up a bowl of soup.” Or, “I didn’t buy them, my friend Jack handed them down to me.” The It person tries to identify the nursery rhyme based on their answers. He may ask the same person a different question three times in row, if he wishes, and their word becomes more obvious. (age 10+)

People I Know

Each player receives three scraps of paper. On each, he writes the name of a person – historical, Biblical, literary, or personal acquaintance. All the scraps are gathered and shuffled in a basket. All players sit in a circle, and two teams are comprised, using every other person. The basket passes around the circle. Each player gets one minute to help his team guess as many names as he can, speaking quickly and using clues. He may say anything he wants, but use no hand motions or parts of the name. A name like Anne Frank might be recognizably easy, but even if the person knows nothing of the name, he breaks it into parts to describe it as best he can. “Who lives at Green Gables? Okay, that’s the first part, and the second is another name for hot dog.” He keeps the papers for any names they guess. When his time runs out, he throws any unguessed name back in the basket and passes it to the next person, who starts describing names for HIS team. The game ends when all the papers are used up, and the teams count their points, one score per paper. (age 10+)

Upset the Fruit Basket

I’m sure you remember this one from your own childhood. A circle of chairs is set, with one chair too few for the number of people. All players receive the name of a fruit – apple, plum, cherry, grape, apple, plum, cherry, grape, around the circle. The remaining person stands in the center, and calls out a fruit. “Apple!” All the apples stand and rush to find a different chair to sit in. No one may return to her own chair. The middleman tries to find a chair too, and whoever is left standing moves to the center and takes a turn to calls the fruit. “Upset the fruit basket!” means everyone finds a new chair. (< age 12)

Four on a Couch

This one is more complex. Each person writes their own first name on a slip of paper and places it in a basket. The names are shuffled and redrawn. You are the name you draw, but it’s a secret. Teams are boys versus girls, because teammates need to be identified at a glance, though some girls may have to join the boys’ team to even out the numbers, etc. All players arrange themselves in a circle: boy, girl, boy, girl. One extra chair is added to the circle, so there is an empty spot. Four chairs in a row are chosen to be “the couch.” The goal of the game is to fill the couch with your own team members. The person to the right of the empty chair calls out a name, and whoever has that name on her slip of paper comes to sit in the chair. These two people trade names. The person to the right of the newly vacated chair calls a name, and the game goes on, with a name trade happening at each call. Names are first called at random, and then with increasing knowledge and strategy. You must remember enough of your own team members’ names to call them up to the couch when you get a chance, and enough of your opponents’ names to call them off the couch. Do you see? The team who fills the couch with their own players wins. (age 13+)

*

I hope you enjoy these games, perhaps for your next honor roll evening or indoor recess. Whatever the weather, we’ll make it together—right? Fingers crossed.

Myth Busting for the New Elementary Teacher

The first day of school approaches. Sharpened pencils, neatly stacked book, organized files, and alphabetically arranged encyclopedias grace your classroom. Everything is clean, shiny, and waiting.

I picture you standing at your classroom door on the first day. You are prepared to see your students; you are ready to begin living your dream as a teacher. This is good! I feel anticipation for you.

As you head into the warp and woof of the school year, you may encounter some “New Teacher Myths.” Those of us who have taught for a few years know that falling prey to these myths can happen quickly. Join me as we bust some common myths.

Myth 1: Never Smile till Thanksgiving

Perhaps we smile a little at this outdated adage. Isn't that how teachers functioned in the olden days? If all else fails, at least keep order? Perhaps.

We do, however, often underestimate the importance of a teacher's smiling face and cheerful presence. While it is not always possible to be at your classroom door when your students arrive in the morning, try to make it a priority. When you are there to greet and welcome your students, you communicate to them that they are loved by you; you are grateful for their presence in your classroom and you delight in them.

Our students need to know we are cheering for them and we want them to succeed. Hugs and high-fives are all appropriate for a little person. A hug and a bit of tender care may soothe the first grader who is missing Mommy. Smiles, hugs, affirmation, or cheerful encouraging words help to establish that positive classroom atmosphere. Smile a lot!

Myth 2: Every Lesson I Teach Must Be Amazing

May I bust this myth for you immediately? This is an unrealistic expectation, nor is it possible. Your lessons will not all be grand. Some of them will flop miserably. But take heart! Tomorrow you will teach Reading and you get to try again!

Playing the comparison game may come naturally when you peek into the veteran teacher's classroom. It appears as if she has props, visuals, and kinesthetic aids for every lesson.

First, remember that comparison is unfair. The twenty-year veteran has had two decades to grow her large, extensive collection of resources and to establish her root system. If you attempt to parrot her, you will find yourself on the path leading to serious burn-out.

Instead, ponder your day and your schedule carefully. Is there one lesson you can prepare that involves some pizazz? Preparing an extensive lesson plan for one lesson a day or several lessons a week gives you a much more sustainable goal than expecting that for every lesson.

Myth 3: I Am In This Alone

Young teacher, you may feel alone but you are never alone. Yes, that bump in the journey, that reality check may come a few weeks or months into the school term. Feelings of incompetence, panic, uncertainty, fear, or anger may surface. How are you to navigate this teaching journey well?

It is easy to cast a glance around at your co-teachers. Their classrooms are running smoothly, they know how to navigate challenging students successfully, and they have tips and tricks for teaching Math. You feel alone because you are still trying to find good classroom routines and it feels like your efforts flop when it comes to that challenging student.

Times of loneliness will come. You may find yourself alone in the school building still preparing for your History class, while the other staff members have departed. Acknowledge and embrace the loneliness. Talk to Jesus. Find a mentor or veteran teacher who can help you gain perspective during moments of reality checks. Be humble enough to ask advice; view the seasoned teacher as a resource, not a threat.

Myth 4: I Must Be Jesus for My Needy Students

Not all teachers encounter this myth. However, if you are blessed with a sensitive, compassionate heart, you will likely find this struggle is real. Perhaps your heart hurts because of a student experiencing neglect, hunger, filth, or abuse.* Some children are deep feelers but have no words to express the turmoil in their inner world. They usually go about asking for your love and attention in undesirable ways.

I know. We have all heard the stories. James comes into Miss Miller's classroom, destined for failure. His parents are divorced, his step-dad beats him up, he's failing in every subject, and he is sullen and depressed. Enter Miss Miller. She loves on and believes in James. In the shadow of her tender love, James begins to thrive, and soars to the top of his class. By the end of that school year, he's even studying a second language! In high school, he still sends Miss Miller notes about how she was his favorite teacher and turned his life around. Last time she heard from him, he was attending the university with plans of receiving a doctorate in Clinical Psychology.

In the honeymoon stage of our teaching career, stories like these can stir our hearts, despite the fact that they are not very realistic. We dream about how wonderful it would be—to be used in such a dramatic way in the life of one student.

Dear teacher, may I remind you that you are not the Savior? You have not been called to redeem the lives of your needy students; you are not that powerful. Yes, ask Jesus for ways to love on the dear little person desperately needing nurture and care. Times of pondering are appropriate. However, when you leave your classroom in the evening, try not to carry your troubled students home with you. (Those of us gifted with mercy are more vulnerable to this.) Place them in Jesus' hands and then go home. Spending your entire evening mulling over student needs takes significant energy and draws from your resources. Your job is teaching academics, not being a savior.

If God chooses to use you in a dramatic way in the life of a student, He may do that. But you should not seek that dramatic moment. Be faithful in showing love, kindness, and patience, and then focus your energies on preparing lessons and teaching well.

*If you know for certain that a student is experiencing sexual abuse, you are a mandated reporter because you are a teacher. Talk to your principal about the system your school has in place for handling situations involving sexual abuse.

Myth 5: Your Students Should Not See You CryIt makes them feel uncomfortable, doesn't it? After all, you are their teacher and you need to remain in control and in charge, right?

I recall an experience I had when in grade school. During one morning singing period, our teacher burst into tears! Initially, I thought this was funny, seeing the teacher cry, but that feeling was soon replaced with discomfort, as she continued sobbing in front of us. Nothing I could do would make her stop crying, and I came away from that situation with a vow that “I will not let my students see me cry because I don't want to make them uncomfortable.”

I have, however, been surprised by some of the conversations we had as a class during moments when I felt emotionally weak. One morning, shortly before the school day began, I received some disturbing news. With school was beginning in 10 minutes, I needed to get in front of my students, tears or no tears. Rather tearfully I greeted my class that morning and attempted to continue with my plans for the day. As I was herding students and chairs out of the building for our outside class, one of my boys paused beside me at the door.

“Miss Kuhns,” he said, “What are you going to sit on?” I paused, realizing that I had forgotten to bring my stool with me, which is what I perch on for outside classes. “I will go get it for you,” he offered, heading back to our classroom.

Perhaps my tears called forth a bit of manliness from my second grader that morning. I have discovered that times of emotional vulnerability can turn into times of sweet classroom bonding when I am willing to be real with my students. If the tears come, embrace them and let your students love on you. They need to know that you are a real person too.

As you encounter these myths or others on your teaching journey, I pray that you will be strengthened for the journey. May the Master Teacher bless you with wisdom and confidence!

Physical Education & Health: Statement of Philosophy and Purpose

This document from Pilgrim Christian School grounds the school's physical education and health programs in a thoughtful understanding of divine creation and human embodiment. We take care of our bodies because they are good gifts from God.

I Have a Question!

“Mrs. Birt, I have a question!” Nelson called out. Nelson has many questions.

When is God’s birthday? What does God look like? What is your name? (It is not Mrs. Birt!)I appreciate when children ask questions as they are learning and show that they are curious and wondering about their world. Children sometimes ask questions when I am reading aloud. “What is a coyote?” “What does ascend mean?” They ask questions related to our lessons. “Why does ‘know’ have a ‘k’?” Asking questions helps them learn, aids in clarifying information, and gives information.

How do teachers handle questions from children? Sometimes I will ask them to find the answer. Renee asks, “Where do I put this paper?” I tell her to read the morning list: “You will find the answer.” I may direct students to reread a page or story to find the answer to a question. I may say the answer. Maybe I don’t know the answer, so I tell them I will look it up. (I need to make a note of the question, so I remember to do that!) We can then have a brief lesson on what I find. Currently I have it on my list to find out how large zebra’s eyes are!

Questions are also a good teaching tool. Teachers ask high-quality questions of their students to spur thinking, begin discussions, direct understanding, and engage students. Questions are a great method of assessing knowledge retention.

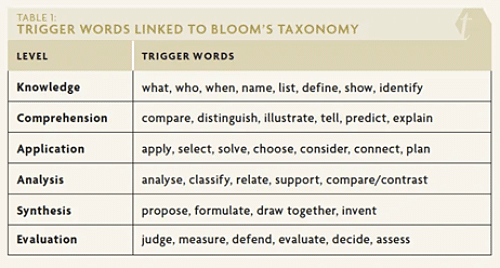

We are studying “Questions and Questioning” in our staff professional development sessions and thinking about the kinds of questions we ask and how we can use questions to grow in our teaching. Some questions are used for classroom management, while other questions ask for information recall, and we need these types of questions. However, for learning purposes, we want to have higher-level questions to develop deeper thinking.

Looking at Bloom’s Taxonomy (table below) can help in developing higher-level questions. The words in the taxonomy can be used to plan quality questions and aid in higher level thinking. On the Evaluation level, use the “trigger words” to create questions of assessing, evaluating, or defending. You can ask students to support their answers with evidence from the text, as on the Analysis level.

Table from Doherty, J. (2017). Skilful questioning: the beating heart of good pedagogy. Impact Journal of the Chartered College of Teaching.

Table from Doherty, J. (2017). Skilful questioning: the beating heart of good pedagogy. Impact Journal of the Chartered College of Teaching.One of our PD activities was reading a text and coming up with good questions. We then asked a colleague to evaluate our questions. I realized that I need to plan ahead on questions. I need to write the questions ahead of class and not try to come up with good questions while I’m teaching.

Teachers may write questions on the board and have students discuss them with a partner for a few minutes before writing or sharing their answers. The students may be required to give evidence to defend their answers. Questions may be used to drive a class discussion, or be included as part of a test or used for morning work. Students may be directed to write the questions.

Here are some strategies for using questions (adapted from Doherty, 2017):

- On the Hot Seat: Students take turns sitting in the ‘hot seat’ and answering questions.

- Ask the Expert: The teacher asks questions of a student on a given topic, and encourages other students to also ask questions.

- Ask the Classroom: Display questions to encourage thinking about pictures or objects in the classroom.

- Phone a Friend: A student calls on a fellow-student to answer the teacher’s question. The first student also gives an answer.

- Eavesdropping: The teacher circulates in the classroom, listening in on groups, and asking questions based on their discussions.

- Question Box: The teacher has a box containing a series of questions. At the end of the day, or end of the week, take some time to choose a few questions for class discussion.

- What is the question? Provide the answer, and encourage students to determine the question.

High-quality questions are powerful teaching tools. Let’s learn how to use them well!

Celebrating the Seasons in the Elementary Classroom: Autumn Ideas

It wasn’t until I started teaching first grade that I began to see the seasonal changes in our world through the eyes of a child. Their awe at the trees changing colors, the plentiful bouquets of colorful leaves they delivered with eager hands and sparkling eyes, and their appreciation of the colorful changes made to the classroom environment made each the transition into each new season an enjoyable one. There are plenty of fall crafts and art projects you can do with young students and most elementary teachers are familiar with those. However, are there other ways besides pasting, cutting, and coloring that will help heighten awareness to the sights, smells, and sounds of a new season? Can we touch on math, literacy, science, and history while learning in the moment?

Plan a leaf raking party

Each year, a parent from the classroom would offer their yard for our yearly leaf raking party. Armed with rakes, the children attempted to rake the leaves into large enough areas to jump into. The children greatly enjoyed the crisp air, working together to complete a task, and the crunch of the leaves as they jumped in the piles over and over again. An added bonus was always the drink and treats provided by the family hosting the party.

Literacy connection: In reflection of the event, have each child share their highlight for the event or write a sentence for each of the five senses. “At our leaf raking party, I tasted… I heard… I smelled… I touched… I saw…” Discuss with your class the items the students wrote that pertain to autumn and usually are not experienced in the other seasons.

Literacy connection: In reflection of the event, have each child share their highlight for the event or write a sentence for each of the five senses. “At our leaf raking party, I tasted… I heard… I smelled… I touched… I saw…” Discuss with your class the items the students wrote that pertain to autumn and usually are not experienced in the other seasons.Make applesauce

Aunt Ada’s American Applesauce

Ingredients:

approximately 10 apples (teacher should prepare by coring but not peeling)

3 T. brown sugar

sprinkle cinnamon

3 ½ c. water

Additional items needed:

paper bowls, table knives, plastic spoons, napkins

Students receive an apple or half of an apple (depending on the class size) and cut apples into small pieces using table knives. Dump apples into an electric skillet with a lid. Allow students to help complete the rest of the recipe by adding water, cinnamon, and brown sugar. Cook until apples are very tender. Dish out and serve.

Math connection: Discuss the measuring cup set and teaspoon/tablespoon set measurements. Have the students arrange them in order from smallest to largest.Literacy connection: Read the book How to Make an Apple Pie and See the World by Marjorie Priceman. Using similar format, write a book as a class entitled How to Make Applesauce and See Berks County (substitute with the county that the school is located).Display the leaves they gather for you

Encourage their exploration of the world outside your classroom by delighting over the nature items they bring into your classroom that they collected while at home or at play. Decorate your shelves, window frames, and desk with the pumpkins, corn shocks, and leaves they bring in. Staple up their handfuls of leaves around your bulletin board. Have the students write things that they are grateful for on the leaves with permanent markers and then dip into beeswax and hang as garlands or make a “We are grateful for…” tree.

Observe the change of a tree seen from your classroom window

If possible, choose a tree that changes vividly with the seasons and that you can easily see from a classroom window. Have the students draw the tree as it changes with each season – now, an autumn tree. Wait several months and direct their attention to it again when it stands bare with no leaves in the winter. Wait several more months and have them note the spring changes. At the end of the school year, draw it a final time in its summer glory.

Literacy and science: Read Tree, Seasons Come, Seasons Go by Britta Treekentrup or A Tree For All Seasons by Robin Bernard and discuss the changes that the students anticipate to see happening to the “classroom tree.”Take local seasonal field trips

Is there an orchard you could visit? A pumpkin farm? A fruit festival? An outdoor cleanup project for elderly neighbors? A colonial village or demonstration that shows how food preservation happened in the olden days? Check Macaroni Kid for events that your students may be able to participate in. Click on the “Change Your Town” tab in the upper right to check for events specific to your local area.

As you experience this autumn season with your students, direct their five senses toward the changes. As they see you notice and delight in the changes, hopefully they too will become active and enthusiastic learners and observers of the world around them.

Granted, I am writing this article from the perspective of autumn in the northern hemisphere. Here in Pennsylvania, we have a distinct and vibrant change from summer to fall. If you are in an area where autumn is not so scenic, you may have to make some changes or adaptations to these ideas to fit your area.

Twenty-Seven Traits of Teachers

Teachers are called to balance accepting the abilities God has given us and pushing ourselves to grow. How did Jesus work with the twelve men that were His disciples? In this presentation, Mr. Lichty explores foundational themes, focusting on traits of teachers and how these affects their classrooms.View the PowerPoint.

Motivated Students: Tips for Active Learning in the Individualized Classroom

I just find myself in the middle of that. They give extrinsic motivation to get them— to bribe them—to do their work. They should be grown up enough to do it because it's the right thing to do. But then I find that I'm sometimes not that either. So what do you expect out of a 10 year old? And it seems like at some point down there, extrinsic motivation is necessary. They should grow out of it. And at what point should you expect them to do that? And I'm never quite sure. So we try different things, but it does seem that by the time they get into high school that are very self-motivated, and most of them are really, really on top of the work and taking it seriously.

What types of extrinsic motivation do you use?

We do a few different things to keep students motivated. One is that, if they get their goals done today, they get an extra 15 minutes of recess tomorrow. If they don't have homework at least four days this week, then they get an extra 45 minute recess next Friday. There's honor roll, a field trip for that. A few different things that it's not been a real big problem. There's always a student or two that you scratching your head trying to figure out how to keep them motivated. And what I suppose you have the same, same deal as a conventional type setting. It's probably different students. Different ones cooperate better with different settings.

What about incomplete homework?

In a setting like this, the homework's not really part of the grade, and so if you don't do your homework, if you just mess around all day at school and don't get your work done, and then you don't do your homework, then what do you do with that? How do you how do you get them to catch that back up and not get farther and farther behind? What do you use for punishment or whatever? And the best thing that I've done is in the last few years, I decided to attach it to the to the test grades. And if they don't have their homework done, it's two percent off of the final test grades in that subject. Whatever subjects that they don't do their homework. That has helped a lot. I give them two free times a quarter. Incomplete homework: no questions asked. No penalty. I know stuff comes up.

How do you answer students' questions?

Yeah. Try not to just give them the answer. There's probably occasions when I'm really in a hurry, and you have the answer, but, you know, usually I just start back at the point where I think they don't understand and ask them questions and try to guide their thinking. Or if they've got the work of all worked out, some of them have this habit of coming up with the wrong things. So they erase all that work, and then they put their flag up.

I say, "No. Leave all your work there. I can see what you're doing wrong, and I know what to explain. I don't have to explain everything about this. You probably understand most of it."

Usually got a sign turned around, or they added when they should have multiplied, or it's just something simple. And I'll tell them what row to look and see if they can find it, find the problem. Or if they just don't understand it, step back at the beginning, wherever I think they don't understand and ask them questions, help them to think through it on their own, and then hopefully that helps. Sometimes just having them read the question out loud is all it takes because they didn't read it properly, or maybe they didn't even read it.

What about the student who is too dependent on the teacher?

I think the best thing to do for them usually is just make them look a little look a little harder. Especially, usually it's more like social studies, that type of thing. They're supposed to read the text, and they're supposed to find the answers. And now they read a reading story, and here's a reading question, and they're supposed to answer it.

Well you answer their flag and say, "OK, where did they talk about— where's this in the story?"

The story is 10 pages long. I'm not gonna stand there and read it.

"Where do they talk about it?"

"I have no idea."

"Well, then you did read the story good enough. You have no idea where they even talked about this. Read the story again. And if you still didn't find it, put your flag up. But at least you got to give me the page where they're talking about it."

Or if I think they... I may, I may narrow it down: social studies textbook or something. I may say it's on this page or this column, but try to try to help them understand they're not going to give free answers. They need to put forth effort. But I try to guide them to at least the right place to look.

First-Grade Journals

At the moment the first-grade journal period is filled with stories of train “drivers,” swinging with friends, playing doll, fishing, and kayaking. Today one student was putting out a fire. Another one was playing with his dog while his younger brother sold apples and apple cider at a stand and his sister made apple jam to sell. Many of their stories are fiction while some are autobiographic. Some of these beginning writers have struggled to come up with a subject. Some of them have so many stories that they don’t know which one to journal about. These young authors have only had five weeks of school but most of them are already enthusiastic journal writers. (I’m using the term “journal” loosely. It encompasses any material that is composed during our journal class.)

Since we aren’t very far into the school year, you may be wondering if first graders are capable of journal keeping. While they may not yet be able to write the words on paper themselves, yes, they can keep a journal. Most young children love to tell stories. Our journal class is a means for putting their stories on paper and sharing them with others. For the first several months of first grade, the students draw their story and dictate a sentence for me to write on their paper. We then have a sharing time when they stand up and tell about the picture they drew. As first graders learn to read and write they can start writing labels on their pictures. Eventually I require them to write something about their picture. We end the year with a storybook that they have written and illustrated as an accomplished author and illustrator.

There are several benefits to starting this writing process early in a child’s academic journey.

- Creating a positive and non-threatening writing experience early in a child’s learning career cultivates an appreciation and enthusiasm for writing in later years. When a school creates a writing culture, it produces writers. Not every child will embrace the writing experience whole-heartedly but there are fewer groans and complaints of “I don’t know what to write about.”

- Starting to write early in the school years aids the child’s ability to develop clear communication skills. The more a child practices a skill the better he becomes at it. Introduce writing early enough that they become good communicators before they are graded on how well they communicate a thought.

- Children are creative. It has been stated that children are creative until they go to school and then school takes the creativity out of them. It doesn’t have to be so. Allow them to use the writing period to express their creativity.

- A main benefit that I see coming from early writing classes is the development of language and thought process. Children need to learn to tell stories in proper sequence. They need to learn to use complete sentences in oral and written communication. With the proper guidance and prompting, first-grade journal classes can help students organize their thoughts into coherent ideas. When a child has had practice dictating sentences to someone, it becomes easier for them to put their ideas on paper when that time comes.

We journal twice a week on set days. When it is part of the weekly schedule, students are less inclined to view it negatively. Most often I allow students to journal about whatever they would like. Once they become familiar with the routine, many of them start to think about what would make a good story in advance. In the week of Youth Hunting Day, several of my students came to school with hunting tales. They are primed and ready to put their stories on paper. I find that most first graders will journal about real happenings in their lives. A few will use their imaginations to concoct fictional tales. There are usually a few children who have difficulty coming up with something to journal. Then it is helpful when the teacher knows something about their life outside of school and can help give suggestions. It can also be helpful to have a list of ideas to write about. Some years I give out a story prompt that the student should use if they have not already chosen a topic. And sometimes I tell them that we will all be writing about the same thing. I usually need to warn them in advance if I require a topic. If I spring it on them at the last minute some of them will be disappointed that they can’t write what is on their minds. Some children have difficulty deciding what to journal about because they can’t draw the subject, or they can’t spell the words. I stress doing the best that they can because my dogs look pretty funny, too.

As we go further into the year and the spelling skills grow, I start requiring students to write their own words. At first they can simply label the picture. Then I require a sentence. As the ability progresses, I start urging students to produce more words and sentences as we slowly transfer from pictures to text. By the end of the year, my goal is to have the written words more prominent than the pictures.

Spelling is always an issue. Students are quite capable of wanting to write words that they can’t spell. I deal with this in two ways. First of all, I allow invented spelling. I also keep an index card for each child on which I write down the words they ask me to spell, unless it is a word they can sound. Many students will need the same words over and over so if you keep a card that they can reference, it saves you time.

I am not looking for perfect spelling, perfect structure, or perfect grammar. The main requirements for the end of first grade are that the piece begins with a capital letter, ends with a period, and names are capitalized. If I have time, I like to look over the written journal piece with the child. We look to see if there are other places to put periods. We may weed out some ands and thens. I may help them correct the grammar. I guide them into using complete sentences. I may have them fix some spelling errors. Usually this does not happen for every child, every time though I try to get around to each child every couple of sessions.

There are two components of a journaling class that help create enthusiasm and purpose for the writer. First, we start the class with a short story that I usually read to the students. Or, I may tell them a story. I choose well-written and classic stories. I also use this time to introduce them to the various story genres: the folk tale, a tall tale, fairy tales, tales from other countries, true tales, Bible tales, and story poetry. When possible, I use a book that is well-illustrated. Just as important to the young child is the sharing time. When we are finished with our journals, each child gets to stand up in front, show his picture, and share his story. Most children learn to enjoy sharing their stories. There are usually a few shyer students who need to be coaxed into telling their story by questions from the teacher to draw out the details, but after a while they are comfortable sharing also.

In the presentation part of journaling class, we talk about how to share the story and we also talk about what the listener does. A good listener pays attention to the speaker. He also does not laugh (unless the speaker means for them to laugh) or make uncomplimentary comments about the ability of the one sharing. This part of the class needs to be a safe time for all the students.

Our journal stories are kept in a personal ring binder that grows through out the year. Students enjoy seeing their progress and parents enjoy paging through the binders when they visit school. For many of the students, these pages have become a first-grade keepsake that they bring out and chuckle over in later years. And, some students have discovered an enjoyment of writing that goes with them through their school years and into life.

Textbooks - new/unused

- Unopened BJU 5th ed. Biology Teachers version - $40 (1 available)

- New/unused BJU 5th Ed. Biology Test key (1 available)

- New/Unused ABEKA 2nd ed. Science: Matter & Energy - $15 (1 available)

- New/Unused ABEKA 5th ed 9th grade Grammar and Comp. Quizzes/Test - $4 (7 available)

- New/Unused ABEKA 5th ed 9th grade Vocab/Spelling/Poetry - $6 (3 available)

- New/Unused ABEKA 5th ed 9th grade VSP quizzes – $3 (3 available)

- New/Unused ABEKA 4th ed 9th grade Themes in Literature - $10 (2 available)

- New/Unused ABEKA 4th Ed 9th grade Themes In Lit Quizzes/Test - $3 (20 available)

Ready to Meet? How to Prepare as an Attendee or Chairperson

If you're on a school board, and there's a meeting coming up, you should read the past minutes. You should really get familiar with the past minutes, especially the previous meeting, possibly one or two more. Get familiar with the past minutes.

If you've been assigned some work, some research work, perhaps, be sure it's done. You have an obligation. You were assigned that work. You you agreed to it.

You need to get your homework done. Read and ponder the agenda, if there is an agenda—and a school board meeting should have an agenda. Not all meetings will have agendas. I'm not going to unpack that too far. In the business world, we sometimes have meetings that don't have agendas by design. School board meetings should have agendas, so if there is an agenda, get familiar with it.

Now, if you're the chairperson, prepare for it. And there's a couple extra things for you that matter. You know, as a chairperson— and I'll just share some personal things on this point. As a chairperson, what I will do in my life is very kind of driven by calendar and by schedule, so I will literally carve out of my schedule. I'll carve out thirty minutes or forty five minutes to prepare for a meeting. What I call that is a meeting with myself to prepare for a meeting. This is when I read the past minutes. This is when I become familiar with the agenda. This is when I think about the setting. This is when I would email all the attendees to say, “Just a reminder, we're going to we're going to meet at seven thirty, you know, at the school or whatever.” This is when I kind of do that prep work. In that reminder message, I would suggest that you should send out a copy of the agenda, either in the body of the email or in attachment—attachments are nice for this— as well as previous meeting minutes.

Highlight names for people that that have specific action items. Call them out in your agenda or in the body of your email. List the agenda items, the leftover ones from a previous meeting. So be sure to review the past. What's left over, what didn't we conclude? Be sure to list those.

In the school setting, think about agenda items that are more seasonal in nature, programs, for instance, that happen annually that need to be discussed: school picnics, school trips. Some of these things are seasonal. Get them. Think about that. Get them on there so that they're not kind of an afterthought at the meeting: “Oh, yeah, we need to do this as well.” Try and think about the seasonal things that that, yes, are repetitive, but that the need to get on to the agenda.

You're the chairman. You're driving the meeting. You own the agenda. Agenda items are interesting. If there's agenda items that require a decision, note that on the agenda. What is the outcome of this agenda item, this particular item? If you know that we need a decision at the end of this meeting, note it so that the discussion can kind of launch from that premise. We need a decision, or alternatively, if you know that this is discussion only, decision later, maybe note that on the agenda so that the attendees’ expectation is set.

Here's the caution. Be careful as a chairman. Be careful not to impose your agenda on the agenda. This can happen in a very subtle way. You need to be deliberate about not doing this. Solicit agenda items from others. This could come from staff, probably will come from staff. You own the agenda, but seek agenda items from other staff. Seek agenda items from other board members. You can do this in your kind of reminder messages, or you can do it at the beginning of the meeting.

As a chairman, you're responsible to to choose the setting. So pick the time of day, the location, all of those things that match the meeting and the style of meeting that you want. All right. I'm going to move into more of a little bit more on format and setting. Format and setting is important—how you maximize your efficiency of meeting, how you maximize the potential outcome of the meeting. These things are important.

Meetings should be organized and prompt. It's the chairman's responsibility to ensure meetings start on time. This is basic stuff. It's his responsibility to make sure everyone's comfortable. Do we have enough chairs? Are they comfortable? Are they too comfortable? It's his responsibility to make sure the setting is correct.

Interesting thing on dress code, and I've observed this over the years. Be formal about your formal meetings. There's actually value in this. As you allow your dress code to kind of go from formal to informal and almost to the point of no formality left, the meetings will tend to follow that trend. The discussion will tend to follow that trend. There's a time to be formal and there's a time to be informal. Meetings should, in my opinion, have a formal component, including dress code. It changes the dynamic of your meeting, and there's something really healthy about that.

How you sit is important. Everyone should be able to see each other. If you're using a room, try the best to match the the room size to the group size or the group size to the room size. Don't have five men meeting in a gym. Right. You can do that, but it changes the dynamics. Also don't have 15 people in a 10 by 10 room. Right. I mean, try and match the group to the room sized. Tables are the best. I'll even go as far as, say, that oval tables are better than square tables. There's actually a reason for this. People can see each other better. I've observed this in the business world. The shape of the table makes makes a difference.

Everyone needs to stay alert, but the chairman, like probably no one else, needs to maintain alertness and composure throughout the meeting. He needs to position himself in such a way that he can see everyone around the table very well. Maybe it's a circle. Maybe you don't have a table. And then there is, I understand, a range of schools and school settings. And what I described is kind of the optimum. But you can dial it back and change it up if you have to.

Board meetings, I believe, should start with some inspirational thoughts or even a devotional. We don't need a lengthy devotional, but something that's really punchy and inspirational at the beginning. Start with a prayer. That's very, very fitting.

As a chairman, you should preface every meeting with a short vision statement. If your organization has a vision statement or even a short term goal, something you want to achieve in 2019, you should preface your meeting with that statement. In the school setting, you might have a vision statement. You might have a sentence or two that simply encapsulates why we do what we do. Start the meeting with this. This is powerful. I've seen this. I've seen this in the business world where, as a leader you, you start with that. You preface every meeting with "this is why we're here." It's going to feel like you're over communicating. You're going to hear yourself say this over and over and over. And by the time 2020 rolls around, you've going to have said this hundreds of times. It's actually powerful. As you move through the meeting, you will come back to that. That vision statement becomes a filter for every decision we make. Does it meet the criteria? Does it meet the test? Does it actually do what we said we're going to do? Will this decision enhance our vision?

I would highly suggest we adopt that in our board meetings. I believe that all meetings should have an anticipated end time. That doesn't mean that every in time is carved in stone. As you move through a meeting, whether it's in the school setting or in a business setting. There are times when we when we go over time, there are times when we close it off early. But set the expectation. As the chairman, I believe it's healthy for you to actually take a minute and say, "All right, group. We have these agenda items. What can we agree to for an end time? We're starting at seven o'clock. Can we end by ten o'clock? Is that reasonable? Let's agree to it.” I like doing that as a chairman because it helps me to stage my discussions.

As a chairman, you are managing the meeting. It's not your agenda. You're driving it, but it's not you and only you. When you look at the agenda, I don't necessarily advocate taking them line by line by line. If you have ten items on your agenda, and that's likely too many, but if you do, they're not necessarily listed in order of importance. So if we get to ten o'clock and it's time to quit, which of those ten can wait till the next meeting? Decide that before you get to ten o'clock, take 30 seconds at the beginning of the meeting, and agree is a group which of these items are the most important and which could wait if we run out of time? So the way this works is, is you have the agenda. I just take a pen and I write in. I seek the group kind of input. Which ones are first, which ones do we want to tackle first? And we itemize them, and we go through them in that in that order. Sometimes we juggle based on conversation, but I like to take thirty seconds at the beginning of the meeting. It gives structure, and it gives clarity as we move through the meeting.

I've said this before, but be crisp and clear as you enter into an agenda item. What is the anticipated outcome? "Gentlemen, we need a decision." Or, if that's not the expectation, "Bretheren, when we're done, we are not going to reach a decision. We are going to plan to not reach a decision, but this is long term. "We need to think about this. Let's talk about this for the next 15 minutes. I want you all to share, and we're just going to engage." If that's the expectation set the expectation before you enter into the discussion. Is the outcome of this discussion a decision or is it simply a conversation to set the stage for a future decision?

I've been to meetings where the secretary does minutes on a laptop in real time, puts it up on the screen. Some of that is good. I've wondered already if that's more of a distraction for us than it is a help for us. At board meetings, I would be I would probably hesitate to put those minutes up on the screen. That's just my experience. I don't feel strongly on that.

Freely share your own ideas, but don't be afraid to openly challenge your own thoughts. If you're a person that's quick to talk, be conscious about this. Be deliberate about nudging others to speak up. You can say things like, "Hey, Joel, I haven't heard you say something for the last ten minutes. Before we make a decision on this, I'm really interested in hearing your thoughts on this. I don't want to put you in the spot, but I'd love to hear what you got to say." This helps kind of kind of generate healthy discussion and sets the premise for challenges, because that's what we need to do.

I believe the chairman should be slower to speak. He should not be the first one to share his opinion. He should be slower to speak. At the same time, he shouldn't hold back when the time is right. He should be more conscious of giving opportunity to everyone else than he should be about sharing his own, his own opinion, but not hold back when the time is right. You don't want to stifle conversation and input from others just because of who you are and because of your trump card. You need to be very aware of this.

Just imagine you're at a meeting, you're in an intense discussion, conversation, conflict, if you will, and there's an impasse. We have five men. Three of them feel one way. Two of them feel the other way. These things can happen where there's strong opinions, and they're polar opposites, if you will. There's nothing really wrong with that, but how does how does the chairman handle that? One suggestion I would have is when you, especially in the school setting, where we are brethren. We sit there. We understand that in the multitude of counselors there is safety. We all want the best outcome. Stop, have a little prayer meeting, go around the group, everyone prays from their heart, and then start up again.

The other one—and I've never I've never seen this happen at a board meeting. I have set the stage for this to happen in a business setting. I've also never done this in a business setting, but I believe it would work. So I need to be just up front with that. We had a meeting where there was multiple there was a few different departments sitting around the table. The discussion involved a topic where there was a lot of protection of turf going on. And because of that, it was passionate and got kind of personal. There is really no right or wrong, but we had we had to come to a united kind of agreement. There was good, healthy conflict going on, but it wasn't moving forward.

Finally—I was chairing the meeting—I said, “Look, what we're going to do is I'm going to give it another five minutes or so. If we don't if we can't kind of get to get to an agreement, what we're going to do is everyone is going to get up, and you're going to rotate by one chair, and you're going to pick up the position of the person who's chair you are filling.” Now, these people weren't throwing things at each other. It was it was healthy. It was good, but it just wasn't moving. We had to shake things up and move it. There's other ways. Sometimes you need to stop, stretch. Sometimes you need to postpone.

Ask yourself, do we need to make a decision on this, or would more information be helpful? Many times, it's not. Many times, we should make a decision. A successful meeting always ends with results where actions are taken.

To the chairman personally, leave some time. If you need to be done by 10 o'clock, wrap it up at quarter to ten and then start summarizing. And if you need to, reach out to the secretary, and say, "Mr. Secretary, read us the official minutes as you recorded this decision." Ultimately, it's going to go on record officially how the secretary wrote it. Be sure everyone understands the decisions in the same way.

If you don't have clarity leaving the meeting, you're soon going to be in defense mode. The summary period is critical to clarity. There's so much that we can learn from kind of doing things right at the end of the meeting. There's been good meetings that I've attended that have ended badly because there was no kind of summary and wrap up and action. And that's sad because there's a lot of energy that went into making decisions. But then the ball was kind of dropped.

School Has Started!

“How was your second day of school?” I asked a new teacher.

“Not so good,” she replied. “I’m finding more things I need to learn and figure out.” She wondered how my day was. I noted that it was going well, but I was very tired. She agreed and wondered how long that lasts. I told her it was usually a couple weeks until we were feeling adjusted and not so worn out from the days at school. I remember going home and just lying on the couch, reading and resting. The new teacher found it comforting that even after 33 years of teaching, I am still exhausted at the end of the second day of school. She was also consoled by the fact that I still make mistakes, even after all these years of teaching.

I chatted with another new teacher. She was beating herself up because she had messed up with one of her classes. We talked about it—“We all make mistakes” and “This was only your first time – give it some time.” “Give yourself grace!” We need to give ourselves grace as we begin the year and learn new procedures and methods.

To the new teacher (and experienced teacher, as well!) I would like to share things I’ve learned in my years of teaching. I have learned from the new teachers, too. Take heart, new teacher!

Be open to learning and receive teachable moments for yourself.

A new teacher and I were discussing one of my students with whom we both work. This child needs a lot of supervision. I shared a lesson I’ve learned: “Praise publicly; correct privately” and that this can be challenging to do. I felt bad because I did call out this child’s name in front of the whole class. He was tipping his water bottle over someone’s head and I called him out on that inappropriate behavior. The new teacher was concerned then because she had yelled at some boys as they ran out on the soccer field. We agreed that sometimes we have to correct in front of the class, depending on the situation, and she commented, “I want to make it a teachable moment.”

Ask questions; ask for advice.

Most people like to share and feel affirmed when you ask questions, so don’t be afraid to ask. “Where is this supply kept?” “How can I prevent so much talking from the students?” “What do you do when….?” Experienced teachers are willing to help and guide new teachers, I’ve found.

Be open to corrective conversations.

A new teacher asked how to handle a situation. She hoped she could learn from someone who had dealt with the same thing.

Watch a more experienced teacher.

The first day of recess, the new teacher went outside with her class so she could see the procedures for lining up and coming inside. She said she wanted to watch the procedures and learn from the way the experienced teacher did it.

Ask someone to check over your communications.

It’s helpful to have feedback from someone else who has been communicating with parents and students and knows the families. Ask if you’ve included all of the needed information and how your writing might sound to families. Communications reflect on the sender.

Enjoy your days!

I asked another new teacher how it was going, and he commented, “I can’t wait for the weekend.” I understood that. I was weary, too, and looked forward to the weekend schedule.

Make sure to take some time to rest and relax, and not “live at school.” I know this can be hard. After 33 years I am still at school late many times. Sometimes I just have to stop working. I used to change bulletin boards each month, but one year when I was very busy I did not get that done. I realized that nothing bad happened because my bulletin boards were not changed! I needed to let some things go.

The new teacher shared that everyone has been so helpful and supportive – thank you to staff for helping new teachers, and to new teachers for joining us and working together!

Blessings to new and experienced teachers in your new year of school!

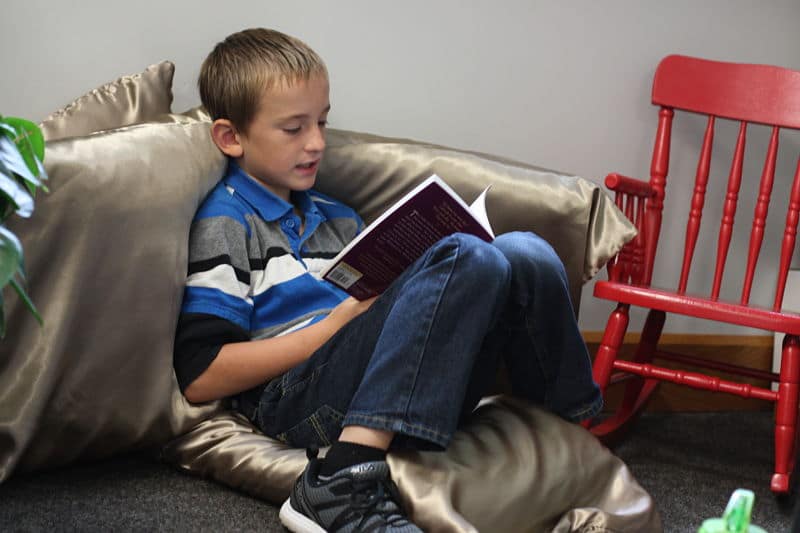

Teaching Fluency through Choral Reading

One of my memories as a seven, eight, and nine-year-old involves reading to my little sister for hours at a time. Naomi was five years younger than I and must have been a remarkably patient listener. I remember reading many of the Thornton Burgess and Laura Ingalls Wilder books to her. Apparently, I’ve forgotten all the other books I read to her because my mother says that when Naomi began to read to herself, it was years before she read many books that she hadn’t already heard.

As I observe some of my third and fourth graders stumble and sweat while reading aloud, I wish each of them, too, had an eager little sister to listen to them for hours on end. When I read to my sister for the sheer delight of enjoying the stories together, I didn’t realize that these experiences were also preparing me for rapid, comprehension-filled, independent reading. These are the precise skills I’m hoping to build in my third and fourth graders.

I can’t replicate with each student the same rich oral reading encounters I enjoyed, but I can encourage them to read at home to their little siblings by sending home fun read-aloud picture books. In my classroom, I can offer other opportunities that are especially helpful to my challenged readers, such as choral reading, the practice of reading aloud together as a group.

As I’ve listened to students read orally by themselves, I’ve learned to predict which students will struggle with choral reading. They’re the hesitant readers who misread small words, struggle to chunk bigger words, and read in a choppy manner. During choral reading, these same readers may mumble along and not follow the text with their eyes. These behaviors indicate that these students are not gaining desperately needed reading skills through the practice of choral reading. These are precisely the students who need focused, intentional choral reading the most.

I’ve found that poetry reading, Bible Memory practice, and reading directions are three simple ways to integrate choral reading in my class. The mundane practice of reading directions orally offers an opportunity to grow hesitant readers into confident, expressive, and smooth readers.

Following are three engagement techniques for reading directions that help me to pull in those hesitant readers. You will need to adapt and adjust these techniques to your situation, but I offer the specific language and techniques I use for two reasons. Firstly, I want to emphasize how consistent and explicit your instructions need to be. And secondly, I want to be clear about how critical it is to require 100% participation of your students. The benefits go way beyond reading class.

Rhythmic Beginnings

I make sure students are sufficiently cued to focus in on the directions before we begin. It can be more complex than you would think for some students to engage their eyes, voices, and minds all at once, but that’s what’s required to read and absorb directions. I find that when we start together, we can stay together. So I say something like, ““Let’s read the directions for number one aloud together. Rea-dy, begin!” I try to be very predictable, saying the same thing at the same rate each time. I explain to students that when I say “ready, begin” they should be taking a breath so that their voices are ready to start immediately. We read the directions with my voice slightly leading theirs, both in volume and pace. In a week or two, I can abbreviate my instructions to “Number One, REA-dy, beGIN!”

Without a rhythmic beginning, I would estimate that only about half of my class is ready to read the directions. When I include a rhythmic beginning, I find that typically about 80% of the students are with me as we read the directions. The problem is that this still leaves 20% who are somewhere else, and this last 20% of the class is the group of students that most need choral reading to develop their reading fluency. They won’t benefit from this critical reading activity unless I can engage their minds, eyes, and voices as well.

Nonverbal Prompts

As I say, “Let’s read the directions…” I move toward a student who is disengaged and I point to the directions in the book to focus the student’s eyes and mind. As we begin reading, I listen for that student’s voice. Unless I can hear that voice, I take my nonverbal prompt a step further, leaning down and reading into the ear of that student. Usually at that point the student engages, which results in a big smile and thumbs up from me. It only takes a few weeks for these nonverbal prompts to pay off. My consistent awareness of that student’s engagement and my nonverbal prompts, which consist of pointing to the text, reading in their ear, and responding with great joy when I see improvement, results in almost 100% of my students engaging in the process of reading directions together.

Individual Conversation

Individual Conversation

But there are still a few students who either do not read my cues accurately or do not understand the necessity for complying. In either of these situations, a private talk is probably necessary. I usually start by saying something like, “I’m so excited by what happens to our minds and to our ability to read aloud smoothly and well when we all read directions together. I’ve been concerned though that you’re not getting a chance to grow as a learner in these ways because I’ve been noticing that I can’t hear your voice and I can’t see your mouth moving when we read directions. Can you tell me why that is?” After giving time for a response, in which some students will insist that they are helping to read directions, I will reiterate that the only way I know if they’re helping is if I see their mouth moving and am able to hear their voices when I bend down close to them.

After this, I find that these students learn to comply over time especially if I do two things. First, I gently remind them of our conversation by commenting to the whole class about the value of reading for fluency. “Class, I like how I’m hearing each voice helping with the directions. That tells me you’re growing as a reader. Over time, you’ll find that you can read aloud more smoothly and quickly and that’s because of these little things we do like reading directions together. Great job! Be sure you’re always ‘Jonny on the Spot’ and ready to read!” Secondly, I follow up with that student by “inclining my ear” towards them as I am commanded to do in Isaiah 55:3. This reminds the student that I’m listening for their voice. In response, the voice of the student rises in volume, focus improves, and mumbling stops. Now the student can begin the process of gaining better oral reading habits.

A recent study recorded sixth grade students making progress in gaining smooth, expressive, and rapid oral reading through engaging in as little as sixteen minutes of choral reading per week.

This study and others have profoundly impacted my thinking about choral reading, causing me to experiment with ways to increase the effectiveness of my students’ choral reading experiences. We don’t have hours to sit on couches and read aloud to patient little sisters, but I’m learning to maximize the oral reading we’re doing throughout the day, creating richer, more engaging opportunities for practice, without needing to carve extra time from other subjects.