All Content

Education's Purpose

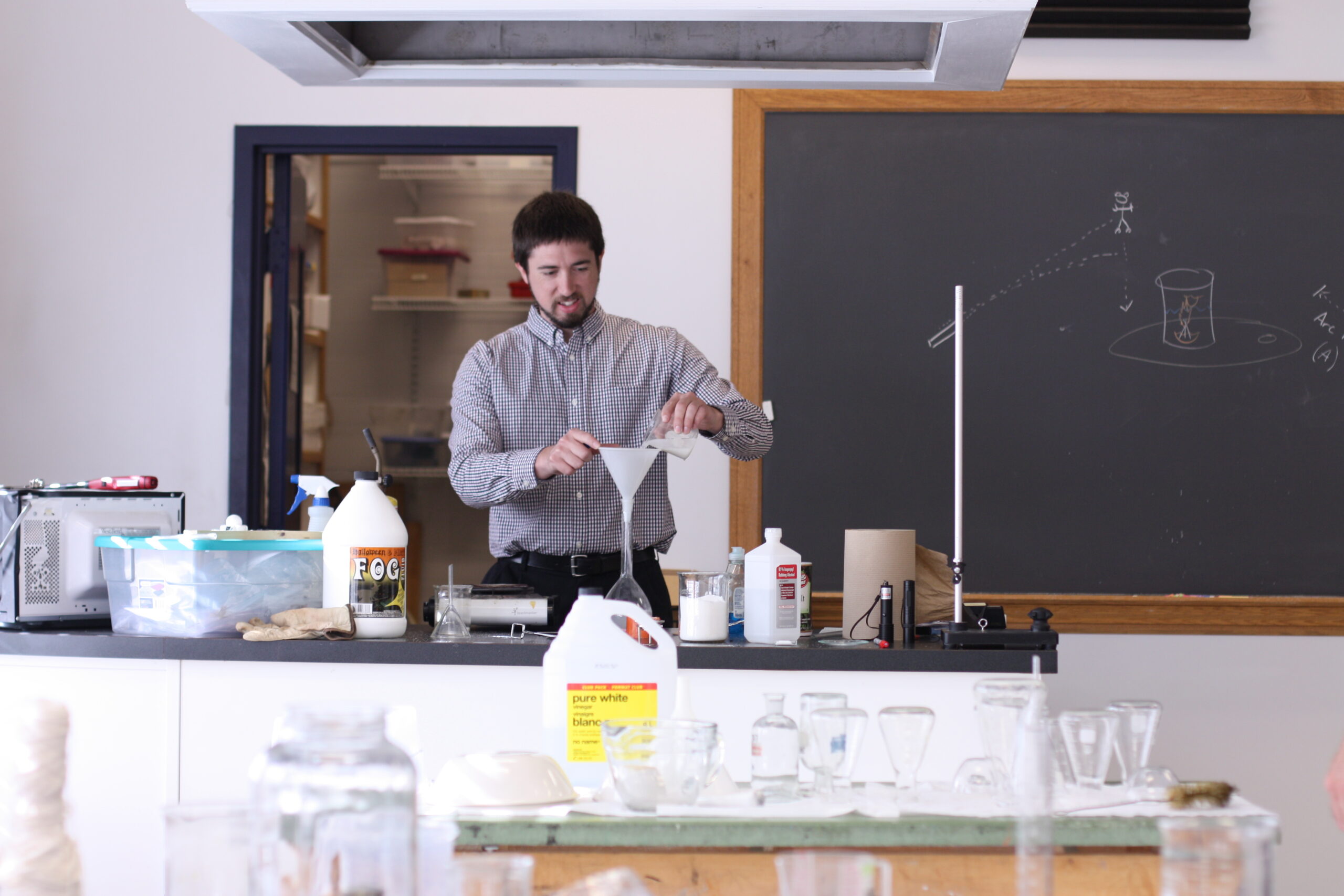

I have long been fascinated with Booker T. Washington and his methods of education as displayed at the Tuskegee Institute in the late 19th century. Washington firmly believed that education, especially for the African American race at that time, was to consist mainly of practical knowledge and skills that could be used to build up and better the life of his race.

A popular notion of the day was that the ultimate life was one of avoiding hard work. However, Washington opposed this idea strongly and taught his students that there was beauty and dignity in hard work. In his autobiography Up From Slavery, Washington said this:

“From the very beginning, at Tuskegee, I was determined to have the students do not only the agricultural and domestic work, but to have them erect their own buildings. My plan was to have them, while performing this service, taught the latest and best methods of labour, so that the school would not only get the benefit of their efforts, but the students themselves would be taught to see not only utility in labour, but beauty and dignity; would be taught, in fact, how to lift labour up from mere drudgery and toil, and would learn to love work for its own sake” (Washington, 1901,p. 148).

His students constructed most of the buildings at Tuskegee. They dug the clay and fired the bricks themselves. They experienced an incredible amount of hardship in this process, but Washington persevered and his school succeeded.

While I am fascinated by Booker T. Washington and his educational philosophy, I do not believe it encompasses the entire purpose of education. But because of the situation of his people at that time, I believe his purposes were entirely appropriate.

For the situation of my people in our time, I believe that education’s purpose must be to inspire the oncoming generation to follow the first and second commandments: to love God and neighbor with everything. There is nothing more important.

This focus does not exclude the regular academic disciplines; rather, it lends a powerful purpose to them. We see God everywhere we look. All that is true, beautiful, and good is our text, and through this text we see our God and we learn to love him.

As we love Him, we love our neighbor. In school, we develop the tools and capacities necessary to love and serve God and our neighbor with heart and skill.

Reference: Washington, B. (1901) Up from slavery. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. Retrieved from https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/washington/washing.html

You Are Not on Trial: How Parent-Teacher Events Can Strengthen Your Teaching

What's the purpose of parent-teacher meeting, parent-teacher activities? First of all, I believe it's to establish common ground between the parents and the teachers. The second purpose of parent-teacher activities is to create an opportunity for parents and teachers to communicate on a constructive level. Too often, parents wait to talk to the teachers until the teacher is doing something wrong, and vice versa. Teachers wait to talk to the parents until something's going wrong with the student and then we have to call up the parent and that's no fun either.

And lastly, the purpose for parent-teacher activities is to inspire and instruct the community on the importance of school. That's probably more of a formal setting maybe, where you sit down and have a meeting on an evening, bring in a speaker from out of the area, and talk about what school does for your community.

Those are three basic purposes. So, activities, what are some of the different types?

Formal: Instructional Meetings

First of all, starting with the formal, is an instructional meeting. We do this on a Wednesday evening when we would normally have prayer meeting, so there's no excuse for anybody not to be there. [You can talk about] the history of Christian education: how did we get here? What are we doing? Because we're now in the second generation of our Christian schools, and if it's going to thrive, well, that's why you're here today. If you have a vision for it, it's really the only way it's going to go forward, is if the people of your congregation have a vision for Christian education. You can talk about development in the preschool years, so what happens before that child goes to school?

The most recent one we had was "Developing the Desire to Learn," and that was kind of interesting when we brought—I don't know know many know Anthony Hurst. He's taught for many years. He came to our school and did that one. That was fascinating because he's a teacher. He loves to learn. The challenges... What I took away from that one, as parents, our scope is going this way. We're saying, "What can I eliminate from my schedule? How can I free up my life? How can I just do the essential things to make life happen?" And as a child, their life is going the other way. They're saying, "This world is so huge. There's amazing things to learn," and so they're getting into things and exploring things, and so their world's going this way. "What else can I do? What else can I try?" And so, we're trying to bring those two together as parents and students.

Practical tips for working together. Challenges of a small school or challenges of a large school. Somebody from outside your community can come in and address those issues because those can get sticky. That's why it's a good idea to bring somebody in from outside, because they don't know what's going on, but human nature is the same. We're dealing with the same human nature and so they can address those things in generalities without knowing the details of your situation, but sometimes it takes an outside perspective.

It's also an opportunity for the board to give any updates. The chairman usually gives a report on the school. We also give our treasurer time to give an update on what the finances look like and this past time, this last Wednesday evening, he went into some detail about how our finances compare to the finances of private schools in the state of Virginia, which was fascinating to me.

Scheduled: Parent-Teacher Interviews

The second type of activity is personal interviews and these provide opportunity for one on one communication. I taught school for five years and I remember my first parent-teacher interviews. I was nervous. I was scared because these parents are coming in and sitting down on the other side of the desk. What am I going to say? I mean, we can talk about the report card and their grades. What about students whose behavior isn't what it should be?

And I remember my principal telling me, he said, "You think you're nervous? It's not even your child you're talking about. The parents are just as nervous as you are because it's their child and they're the one that's responsible." But now that I'm a parent, I see it from that perspective too.

Neither the teacher nor the parent is on trial. We're not here to straighten the other person out. It's a time of communicating, figuring out what's the parent's perspective, what's the teacher's perspective. There's times when I've had trouble with a student who wasn't applying himself. I mentioned that to the parent and they said, "What's new? That's how he does his chores. It's just his ... It's something we're working on." And so it was a confirmation to me, you're doing the right thing, you realize that you're on the same page as the parents.

Then there are times when you're in the situation where you're not on the same page and the parents have a completely different perspective than you do on what's going on in this child's life. And it's important to realize that we're not enemies; we're not. We may be seeing it from a different perspective, but we're on the same team. We have the same goal and we're working towards the same end.

Another problem that can happen is that we wait until it's a big problem, to get on the phone and call up dad. As a teacher, that's a little bit late because now there's problems with, obviously problem with a student or we wouldn't be calling them, but there's other social issues. There's other pieces and this starts to become a great big problem. It's much easier whenever they're coming on a regular basis to sit down and say, "This isn't a big deal, but it could become a big deal if we let it go. I started to notice this student has this problem. What can you do about it? What can I do about it? What do I need to know?" And so you have an opportunity to communicate and so many of those problems, if you get them when they're small, don't have the opportunities to wreck your classroom.

Another reason for the one on one interviews is that students are very adept at presenting themselves in the best light. Now that's not to accuse them of being intentionally dishonest. But when the student goes home and tells their parents about what happened on this paper, they're going to paint it as much as they can in their best interest. "There's so many other things that went into this, this is not my problem." And so when you have that circle closed, that close communication between the parents and the teacher, the student has a hard time excusing himself because the parent knows where the teacher is at, the teacher knows where the parent is at. And so the student doesn't have an opportunity to manipulate those two.

So it's very important that we have open communication between parents and teachers. How do we make this happen? First of all, plan your meetings. We've already heard about that. Get a calendar, send out your calendar, communicate what's coming up in the next couple weeks. That way parents know. The parents are going to be there, they're expected to be there. Set a time and date for every patron and teacher to be there. And if it doesn't work out for the parent's schedule, tell them to reschedule it. This needs to happen. It needs to be important to both to make that connection.

Informal: Getting to Know Each Other

And then thirdly we have the informal connections. And this can be something like a school picnic, something that the school board arranges, that the parents are there, the teachers are there, but there's no formal time to sit down together. I believe that's important because when it's on the informal level, you get to learn what their interests are. What do they enjoy doing? Who are they as a person? So it takes some effort to connect on that level.

The more you can build that relationship between parents and teacher, the less opportunity you have to have that communication breakdown, [in which] you have the digging in and taking sides.

Fun by the Stack: Great Titles for Beginning Readers

I love books. I could dream them and wear them and eat them for breakfast.

I have a special place in my heart for children’s books. But the hardest age for me to find appropriate reading material for is the emerging reader—the child who is learning to read well, but is not yet up to the challenge of most chapter books. I know plenty of delightful individual books, but they stand alone. My early reader needs lots of practice: ten books, at least.

Here is a list I’ve compiled of easy reads for first and second grade practice and enjoyment. Best yet, everything on the list comes recommended as part of a set. There are at least three volumes of each, and perhaps as many as a dozen. They might be found as boxed sets or in glorious treasuries to savor.

Realistic

- The Ezra Jack Keats books. Prized for their beautiful, collage-style illustrations and simple text, Keats’ books celebrate his love of color, childhood, and quiet adventure.

- I Can Read books (by HarperCollins) and Step Into Reading books (by Penguin Random House). Though these books span a wide range of genres and interests, including many I do not prefer, I look for the biography and history titles such as Harriet Tubman, the Titanic, Moonwalk, Balto, and Roger Williams. They are excellent.

- Patricia MacLachlan’s books, starting with Sarah, Plain and Tall. Machlachlan writes the simplest and sweetest of chapter books, with memorable characters and beautiful settings.

- The Putter and Tabby set, by Cynthia Rylant. What will their neighbor Mrs. Teaberry think of next? All kinds of adventures for every season, between an aging cat and a gentle old man.

- The President biographies by Judith St. George. Also called Turning Point books, though they are not searchable by that title. Insightful picture-book stories that focus on the childhood and lesser-known histories of some of America’s famous men. Her book So You Want to be President? is also fun, a wider panorama of life in office.

- The Robert McCloskey treasury, which includes elements of fantasy such as talking Mr. Mallard, yet is set solidly in the real world of Maine’s harbors and hills. From Blueberries for Sal to Make Way for Ducklings, his text and illustrations are unfailingly heart-warming.

Fanciful

- Mike Mulligan and more. Virginia Lee Burton loved personifying buildings and machines, then telling stories of their exploits.

- You Read to Me, I’ll Read to You. Includes a starter book by this title, plus volumes that showcase Mother Goose, fables, and fairy tales. Mary Ann Hoberman is a modern master of verse for children. These are the best read-together books I’ve found: designed to be read aloud in small sections by a child and partner.

- The Little Bear books, by Else Holmelund Minarik. Little Bear visits his grandmother, gets cold in the snow, and makes a new friend. I love the simple language, and the detailed pictures by Maurice Sendak.

- The Frog and Toad adventures by Arnold Lobel. This classic set of friends learns lessons through the year about life and friendship. Lobel also writes Owl and Mouse.

- If you Give a Mouse a Cookie collection, written by Laura Joffe Numeroff. She plays on children’s love of sequence and connection: What happens if that happens? And what will happen next?

- Dr. Seuss’s classic book set. Underneath a bunch of seeming nonsense rhyme and short vocabulary, Seuss tucked a few life lessons about bullying, contentment, peace, and taking care of the environment.

- The Elephant and Piggie bundle by Mo Willems. These are ultra-easy reads, leaning gently on the illustrations for their storyline and emotion. They’re mostly silly, but focus in on the friendship of two unlikely compadres. Look for the Biggie book collections that contain six volumes each.

- The original Curious George treasury by Margret and H. A. Rey. Who doesn’t love the classic monkey stories about curiosity and mishap? But please pay special attention to whether the book is an original or not. There are only seven stories written by the Rey couple, which are (in my opinion) the ones worth reading.

- Beatrix Potter stories, starting with The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Miss Potter writes with a wide range of vocabulary, which makes these stories great for readers who are ready to grow. “His sobs were overheard by some friendly sparrows, who flew to him in great excitement, and implored him to exert himself.”

- The Poppleton and friends collection by Cynthia Rylant. Poppleton has lots of problems, but his pals are usually at hand to help him out.

- Kate DiCamillo’s Mercy Watson. Speaking of pigs, here is one who likes her toast “with a great deal of melted butter.” She gets into all kinds of trouble in these beginner chapter books.

- The Hat books—a trilogy by Jon Klassen. These are among my very favorite picture books, with the text and illustrations sometimes saying opposite things, for lots of giggles.

What books would you add to the list for beginning readers?

Learning the Right-Brain Way: Visual Strategies to Help Students Remember

In working in a resource room with children with special needs, I've discovered there's some things that help them specifically. One thing is [that we may be] working with visual learners. A lot of kids are auditory learners and you can tell them something, you write it on the board and they can learn it. They learn it with a few repetitions. With some kids, it's like a lot of repetitions and it's just not sticking. I found when I was teaching kindergarten last year, actually, some of my kindergarten students were really having trouble learning the letter sounds and blending them together to make words.

Basically, the concept is that right-brain learners really need visuals to stick with letter sounds, with things that are auditory. For the sound 'o' in octopus, most curriculums would have an octopus up here and 'o' down here. You'd say 'o', an octopus, right? But for a visual child, they're not going to connect that octopus with the 'o' sound and with that shape of that letter.

And so when you have a card that superimposes the letter on the picture, they can connect that more easily. So I started with my kids doing these flashcards, instead of the curriculum flashcards, where the letter is smack on the word. It was amazing the progress I saw just in the first few weeks of doing that. When they knew that this is 'a' and this is 'o', then I would start making words by putting these together and not even just writing letters yet. We just use these cards so they can connect already, they can connect the picture and the sound and start making blends together. But they still have it real visually.

The idea is that they see this picture enough that they get it in their head and they have a picture of that. So if they see the letter 'a' with no picture, they can visualize that apple and be reminded of that sound 'a'.

So that's the idea and I've taken that to a lot of different aspects of learning.

I was familiar with this program by Diane Craft, this Right Brain Phonics Program, and I took the concept. So when you get to sight words that are not phonetical, then you can create stories and drawings that go with the word. For the word 'away', we have like two garbage cans here, and a fan and this girl plugging her nose. The little story is like, "That trash stinks. Take it away from me. Get it away." You tell them this little story and then you show them these flashcards. It's a visual reminder.

Then, when they start seeing this or spelling this without the picture, they are visualizing these two garbage cans in the ‘w’ and they're thinking, “Get that away from me.”

It's hard to keep up with the demand sometimes when you get on to spelling. I'm working with a fifth grader who is really struggling with spelling. He wants to spell everything very phonetically because he knows the sounds. So when you get to harder reading, words are not phonetical. This is really helpful for him. I mean, I just make flashcards and I scribble them down with markers or whatever. I do whatever silly crazy thing I can do on that word to make it come alive and to just get it to stick in his memory. Whatever it is, I don't draw the picture next to the word, I draw it on top of the letters. I highlight letters, I make them different colors, and he really sees those pictures.

Another aspect of that is you want to be encouraging your students. You always make them feel really successful. You never say like, "Oh, that's wrong," or something. You say, "Oh, try again," or, "Are you sure about that?" Then they'll notice it themselves.

If I show them a word, and they can't read it, I immediately will flash them the flashcard. Or if he can't spell the word, I immediately show it to him, always giving him that information that he needs until he can have the picture in his head. For the first few days, when he gets a new word-building Pace, and he has 25, 30 new spelling words, we do a pre-test and see which ones he already knows and we skip those. Then, the ones he doesn't know, we make flashcards for them. Then for the first few days, I just flash the cards and have him spell them. I don't try to make him spell it on his own because I want him to get that picture in his head. I just give him a lot of visual reinforcement. Let him see that card. Then I will start hiding it and saying, "What color is the 'W'?" Or "How do you spell this word?" Then while he's thinking of it, I'll try to ask him to describe the colors or describe the story behind the word or whatever.

Also, he's started to come up with ideas on his own, of how to give himself memory tricks because he's starting to learn this skill and see that this helps him. I hope that in a while, he's able to make all his flashcards himself, and he will come up with things that he knows will trigger his memory and will be effective for him.

When I was in Bible Bee—I competed for several years in the national Bible Bee—the references were always really hard for me to remember. I would use the same concept. I would draw some kind of picture on the numbers or make them different colors.

I guess sometimes with things like a memory verse if you can just make it visual, even if it doesn't necessarily make sense to you, even if it seems silly and absurd, if it's going to make it stick in the child's memory, that's the point. That's going to be useful and helpful.

This is called the Right Brain Phonics Program or Right Brain Phonics Book. It's a whole curriculum. I just bought the reading set. I think there's math helps too, but this is just the reading set. It would come with a phonics book. This has list of words that are big and with lots of color. The special sound or whatever would be in that color and it would also often have the visual cues for them so if they're forgetting that sound, they can look up and have that. Then it comes with the set of alphabet cards. Also, there's special sound cards in that set like 'i' in night, 'o' in cow. They have both different spellings on the same because it makes the same sound.

Then, also these right-brain sight words. This is—it says www.diannecraft.org. She also has some incredible videos about working with right-brain children, working with dyslexic children, ADHD, behavior problems. She has all kinds of incredible stuff, information about how the brain works and what can help these children remember things and succeed in their education.

Open-Ended Math

Over the last several years, I have spent significant time trying to understand and implement the best methods for teaching mathematics--especially to students who think they don't like mathematics. Several ideas have risen to the top, but the very best is this:

Students should be given the opportunity to engage with real problems that require significant effort, but are within their ability to solve.

Put another way, students should engage in meaningful struggle to learn real mathematics.

This ideal is difficult to reach for several reasons. Students do not always have the tenacity to keep going when a question feels difficult. Teachers are busy, and don’t always have time to come up with appropriate questions. It’s easier just to assign the practice sets found in the curriculum. Questions are very difficult to judge—some that appear easy are beyond the reach of students, and others that look complex are easier than they appear.

Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to present challenging problems to students and to give them the opportunity to engage in meaningful struggle as they learn mathematics.

I will not attempt here to answer all the challenges to this approach. Rather, I will point out several resources I have found helpful as I try to come up with challenging but solvable questions for my students.

brilliant.orgThis site offers interesting problems at many difficulty levels. It's a subscription-based service, but offers weekly challenge problems for free. These weekly problems often require solvers to think laterally rather than try to solve the problem directly. Check out their principles and note that this is another way of saying that students ought to engage in meaningful struggle to learn real mathematics.

Art of MathematicsThis project of the National Science Foundation offers inquiry-based "textbooks" (free pdf downloads) on a wide range of subjects from Knot Theory to Calculus. Each book has a “Note to the Explorer” that whets the student’s appetite for the subject at hand. Each book starts with the basics and works up to some very challenging problems.

Art of Problem SolvingThis is a curriculum aimed at high-achieving students. No simple questions here—many of the practice problems come from national and international math competitions. Students are challenged to think outside their normal constraints as they work to solve the problems. The elementary counterpart, Beast Academy, offers the same learning philosophy to younger children.

Phillips Exeter AcademyPEA is an expensive private school in Exeter, NH, with an approach to education that is based on collaborative problem-solving. They've put their mathematics materials online for free. These are written and edited by PEA faculty, all of whom are highly skilled at inquiry-based learning. The curriculum is full of interesting questions. Unfortunately (or fortunately, perhaps), it does not offer solutions to these questions. With no answer key to consult, it forces students to collaborate with each other (and the teacher) to decide whether their proposed solutions make sense.

There are many, many other sources for open-ended questions. When I need to challenge my students with questions of a type they don’t normally see, I cast about on these kinds of sites until I find some that interest me. I have found that these have a good chance of interesting my students as well. With so many free (or nearly free) resources available, I have no excuse to be a dry and boring math teacher.

Five Questions to Ask a Verb: Straightforward Steps to Identify Verb Tense

I have probably used this close to 20 years now.

One of the things that I've used in class is "Recognizing Verb Tense."

They need to already be able to identify past, present, and future tense. So students need to know that. I give them five steps, and those five steps will help them to determine what the verb tense is, including the progressive and the perfect and the emphatic.

So let's try the five steps that Carol gives us. We'll start with this sentence. "In spite of his eagerness, Jacob did feel a shiver of fear as he entered the tunnel."

The first step is to find the verb. And I tell them to find that verb, know what their verb phrase is.

So step one is, "Where is the verb?" And the verb phrase is "did feel."

And determine if the first word in that phrase is past, present, or future. It doesn't make any difference what the sense in the sentence is, because that actually messes them up a little bit. If they look at something that's a perfect tense, it makes it look like it's going to be a past tense. But if they have the word "have," or "has," like "has gone," when you look at the sentence it sounds like it's going to be something past. But "have" and "has" are always present tense. So if they look only at the first word, that determines the past, present or future. And I get them to write that down, because that's the first thing you're going to have is that past, present or future.

Step two: "Is the first word of the verb phrase, past, present or future?" The first word is "did," which is a past tense. And so we write down "past."

Step number three then is to look for a form of "have": "have," "has," or "had." Look for the form of "have," plus a past participle. And if they have that past participle and a form of "have," then it's a perfect tense, and they can write that down.

Step three: "Does the verb phrase contain a form of have plus the past participle? If yes, add perfect." But in this case it does not.

Step number four. If they have a form of "be": "am," "is," "are," "was," "were," "be," "being," "been," and a present participle, which is the -ing, if they have that, it's a progressive tense.

So we continue. Step four: "Does the verb phrase contain a form of 'be,' plus a present participle? If yes, add progressive." But again, this is not the case.

And then the last one is, step number five, is to look for a form of "do" and a main verb. So, "I did do my homework," is a form of "do"—the "did", past form of "do." And "do," in that case, the second "do," is the main verb, and that makes it an emphatic.

Step five: “Does the verb phrase contain a form of “do” + the main verb? If yes, add “emphatic.” And in this case it does, so we add “emphatic.”

And so with those five steps, if they can identify past, present and future, they know what a past participle is, and they know what a present participle is, they can identify any verb tense. It will always give them the right verb tense.

Let's try another sentence. "He had been planning this trip for a long time."

So step one: the verb is "had been planning."

Step two: the first word of the phrase is "had." That's a past tense. So we write down "past."

Step three: we see that the verb phrase does contain a form of "have," plus the past participle. So we write down "perfect."

Step four: does the verb phrase contain a form of "be," plus the present participle? Yes, it does. So we add "progressive."

Step five: does the verb phrase contain a form of "do"? No.

So the tense in this sentence is past perfect progressive.

It's just a logical process. And I see students in tests writing down little reminders in the margin of the test for the steps. The more logical student will like these steps.

In doing the tenses, you start out with past, present, or future. If you have a perfect, that comes next. And if you have progressive, that's the third one. You may jump right from present to progressive, but you may have a present perfect progressive, and that's the order. So the steps are in the order that you would identify, that you would label the tense.

Sometimes they'll say, "Oh, there's a form of 'have.' It's a perfect tense." And they'll want to put that down first. Well, no, you have to decide on your past, present, or future first, and then go to the perfect.

They always blame me for, you know, "Grammar doesn't make any sense. It's not logical." But you give them some clues like this, and it does give some logic to it.

Another Year!

“How do you wash these crayons?” asked a student. I was puzzled—why does she want to wash her crayons? Kayla showed me the box of crayons. It said “Washable Crayons.” I explained that you don’t wash the crayons, rather the crayon marking would wash out of clothing.

There are many new aspects to a new school year. It is exciting to have new school supplies, both washable crayons and regular crayons with still-sharp tips, unmarred erasers, long pencils, and full glue bottles. I like the fresh, crisp look of new textbooks and workbooks. The bulletin boards are smooth and bright and the desks are clean and arranged in neat rows.

A teacher friend said she tells her students to put their noses down and smell those new books. “I love the smell of new books!” she stated. I like the smell of new crayons, and my mom commented on the smell of the school building when it’s ready for the new year.

This summer seemed to be a summer of new things for me—a new phone, new air conditioner unit, new car, and new printer. Some of the old things quit working and needed to be replaced. Now it is time for more new things—a new class, new phonics books, and five new students. On the first day of this school year, I thought, “It’s a new morning, and a new school year!” With teaching, we get a new start each year. I think of things from the previous year that I could have done differently. I should have started these lessons sooner in the year. I should have organized the centers more. I can try to do that in this new year!

Some of the children will come to school with new shoes, new dresses, new lunchboxes, and new backpacks. It’s exciting to have these new things. “Look how the lights blink on the new sneakers!” “I have a new backpack, see?” For my first graders, it is exciting to use the new things, and to bring their lunch to school in the new lunchbox. (One of the first days of school, a child asked at 9:00 AM, “When is it lunch?”)

There are new friends to make in this new year. I told my students that those who came to our school last year should be sure to be friendly to the new students. I need to keep that in mind, as well, and look for the new students in other grades and reach out to them. I should make a point to talk to new staff members, and get to know the new parents.

I think about my vision and goals for the school year—maybe I need a new vision for my teaching and my service at school. I may need to work on my attitudes and develop a new mindset, growing in humility, patience, and compassion.

There are new plans for my class, whether that means new lesson plans for a new group of students, or new protocols required by my school. I may need to do some more studying. I plan to continue as a life-long learner so I can meet the needs of this class.

The first day of a new school year is exciting. It’s exciting for Evan, the second-grader who was up and dressed by 6:30 AM. He was ready for school then, even though his bus does not arrive until 7:45. It is exciting for first-grader Sheila, who went into her parents’ bedroom at 3:30 AM and asked when they were going to get her up for school! It’s exciting for this teacher, who worked at school until 10:30 PM the night before, making sure everything was ready for the new class, and who looks forward to teaching these 28 students who have been entrusted to her care for this new year.

On the first day of school, I like to stand in my classroom doorway and pray for the students, for our class, for my teaching, and for the families represented in my students. One of our leadership team prayed that as we have prepared the building physically for the new school year, so God would prepare us spiritually for the year.

I am reminded of the hymn “Another Year is Dawning,” by Frances Havergal, which I’m sure is meant for the beginning of a new year. However, I think it applies very well to the beginning of a new school year. Some of the phrases are very appropriate for teachers in a new school year:

- Another year is dawning! Dear Father, let it be, in working or in waiting, another year with thee.

- Another year of trusting

- Another year of mercies, of faithfulness and grace

- Another year of progress, another year of praise, another year of proving thy presence all the days

- Another year of service, of witness for thy love